Interview with Julie Spray about her book, The Children in Child Health

Our member, Dr Julie Spray (University of Auckland, New Zealand) talks about her new book, The Children in Child Health: Negotiating Young Lives and Health in New Zealand (Rutgers University Press, 2020).

Q1: What is this book about?

This book is about what children do: the unseen and underestimated practices of children who make lives for themselves in situations of poverty and inequality. Children are often the targets of health policy, but they’re treated as almost sub-human, just passive objects of whatever adults decide to do with them—treated in a way we would never treat adult recipients of health interventions. This book shows that health policy doesn’t come to life until it is brought to life by the children who respond to our interventions in their lives and bodies.

At ‘Tūrama School’, a primary school located in a marginalized community in Auckland, New Zealand, 8-12 year-old children and their families deal with a constellation of health issues stemming from colonization and systemic racism: undernutrition, rheumatic fever, impetigo, stress, family violence, bullying, distress and mental illness. These children share their antibiotics with siblings, harass peers who accept a stigmatized charity lunch, exploit a school clinic for social time and cut themselves with razors to express a social vulnerability that can’t be put into words. These are the children in child health policy— a group of children who feature regularly in public discourse as statistics and stereotypes, targets of numerous NGO or government interventions, but whose voices as people are rarely heard.

Q2: What made you write this book?

I originally set out to study asthma from children’s perspectives. But when I started participant observation at Tūrama School it pretty quickly became apparent that asthma was just one of many issues children were dealing with- it was just one tree in a forest. And what fascinated me was the range of interventions being deployed through the school to deal with all these different trees in the forest – and how few of those interventions seemed to be thinking from children’s perspectives.

In particular, I became intrigued by a sore throat clinic that was put into the school to swab for strep throat for rheumatic fever prevention, and a problem the clinic nurses were facing: large numbers of children were coming to the clinic claiming they had sore throats but rarely testing positive for strep. The nurses thought kids just wanted to get out of class, but they were worried about the cost of all the swabs. So I started talking to kids about rheumatic fever and found out all sorts of things that hadn’t been considered by rheumatic fever policymakers who consulted with parents and but not the children who would actually be using the clinics. They hadn’t considered questions like: do children know what a sore throat is? What happens when children view our scary rheumatic fever campaigns? And what other needs might children appropriate this clinic to serve?

An excerpt from the book:

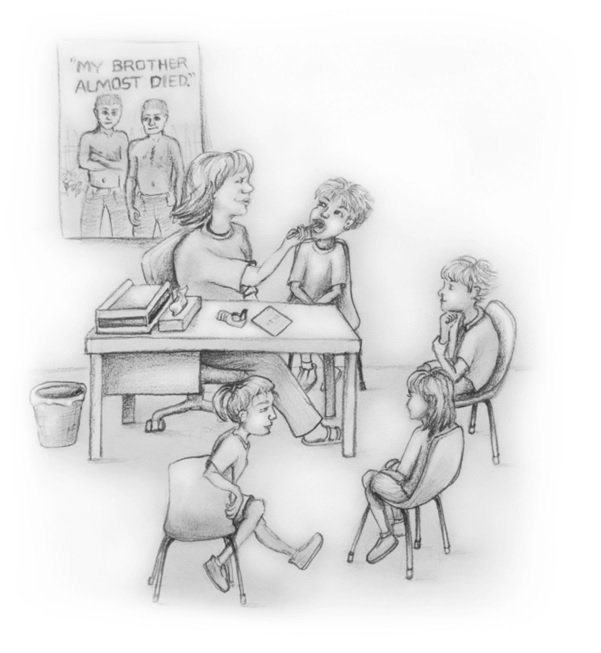

The clinic classroom is set up with three low tables at the back and a bookshelf of books and a few toys to occupy children who are waiting for their turn to be checked. For some children, this is a space to be free, muck around, and talk unencumbered by the policing of teachers. If they get too rowdy Allison will reprimand them, but her attention is on the child she is working with and for the most part the waiting children are left alone until they are called for their turn.

I follow the stragglers into the clinic, where Whaea Allison is finishing up with the last group. The sprinters from Mrs Randall’s class are playing on the ‘spinning’ office chair in the corner, but nine-year-old Dandre heads straight for Whaea Allison’s desk, calling out ‘I’m first!’ Five or six others pull over chairs in a semi-circle alongside Allison’s desk, chatting and joking with her as they watch each other undergo examination. Under the mournful gaze of the two boys in the rheumatic fever poster warning of deaths that started from a sore throat, Dandre weighs himself, helped by other children, and calls out the number to Allison to write down. ‘Do you have a sore throat?’ Allison asks, and he nods, opening his mouth wide for her to check with a small flashlight, and watching as she circles ‘sore throat’ and ‘redness’ on his form. He sits upright, beaming as Allison lets him check his own temperature with the electronic thermometer, and holds statue-still while she swabs the back of his throat—a process all children describe as uncomfortable since it ‘tickles’ and can stimulate gag reflexes (see illustration).  ‘Well done Dandre,’ says Allison; she has a friendly rapport with these children and Dandre basks under her attention. ‘Can I go back to class now?’ he asks, and waves goodbye to his classmates as he slips out the door.

‘Well done Dandre,’ says Allison; she has a friendly rapport with these children and Dandre basks under her attention. ‘Can I go back to class now?’ he asks, and waves goodbye to his classmates as he slips out the door.

When the rest of Mrs Randall’s class have gone, Allison sighs. Earlier, she and Deb had discussed a current dilemma—a large number of children who self-identify as having a sore throat on almost a weekly basis, but rarely test positive for strep. The problem varies by class, and Mrs Randall’s class, along with a couple of the other senior classes, has one of the largest groups of regular clinic visitors. The main issue is the expense; each swab costs about NZ$15 and Allison feels an obligation to manage government resources responsibly. On the other hand, she doesn’t want to dissuade children from coming if they genuinely have a sore throat—the risk of rheumatic fever is real. Yet Allison’s suspicion is that many of these children were just here to ‘muck around’ and get out of class. ‘They go straight down the back going ‘I’m last’—they’re not really here to get their throats checked,’ she grumbles, although this was not the case with most of Mrs Randall’s class today.

This observation is supported by district-wide evidence which shows that while swabbing numbers had increased over the period, the proportion of swabs returning a positive result has decreased (Anderson et al. 2016). It has been noted in the literature that in regular clinics patients will fall within a normal range from avoidant to over-vigilant, and studies of school clinics indicate the same pattern. The term ‘worried well’ describes the 5–10% of patients who seek health care but who are not unwell (Korbin and Zahorik 1985; Lewis et al. 1977). By comparison, over the first seven months of my fieldwork around the same percentage of swabs for self-identified children—9% of 1434 swabs (range: 2–20%)—came back positive for streptococcus A. This does not mean that ninety percent of the time children are well—there are many other causes of sore throat—but these numbers do correlate with Allison’s and my own observations of children in the classroom. While I could not calculate the distribution of swabbing across children at Tūrama School due to privacy issues, the raw number of swabs the clinic took over the course of my fieldwork—3159 from both self-identifications and class checks—works out to average seven swabs a year for each child. In other words: children come to the clinic a lot.

A few days later, Dandre approaches me and asks why I didn’t get him today. Mrs Randall wrote his name down this morning, he says.

‘Because Whaea Allison said you already had a swab come back positive, so she’s going to get you some medicine,’ I answer.

Dandre looks confused. ‘But I have a sore throat today.’

‘Mm yes, but did you have a swab a few days ago?’

He looks uncertain. ‘Yeah I had a sore throat a few days ago.’

‘Yeah, so Whaea Deb is going to give your mum some medicine for you.’

‘But why don’t I need to get checked today?’

‘Because you already got checked, and you’re going to get some medicine soon.’

‘Julie, come play with us!’ Dandre is still frowning as I am pulled away.

Dandre’s anxiety on this day is what first prompted me to really wonder about the nature of children’s engagement with the clinic. It did not seem as if Dandre just wanted to get out of class, although I could also see what the nurses meant about the children who played and joked and tried to extend their time in the clinic as long as possible. It was not until I began interviewing children later in the year, however, that I could start to interpret how their practices of attending the clinic might be shaping, and be shaped by, their production of illness knowledge.