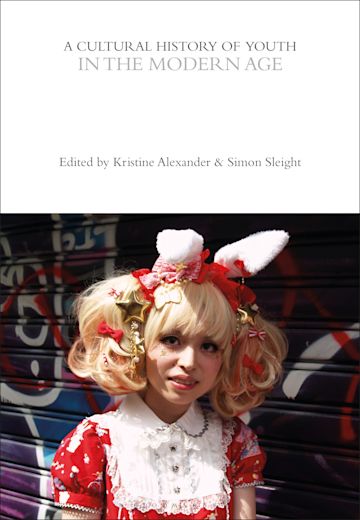

Interview with Kristine Alexander and Simon Sleight about their edited collection, A Cultural History of Youth in the Modern Age

Our members, Dr. Kristine Alexander (University of Lethbridge, Canada) and Dr. Simon Sleight (King's College London, UK), talk about their edited collection, A Cultural History of Youth in the Modern Age (Bloomsbury, 2022).

Q: What is this edited collection about?

This book examines the history of youth between 1920 and 2020. Taking readers from the aftermath of the First World War to contemporary concerns about Covid-19 and the climate crisis, A Cultural History of Youth in the Modern Age is the final instalment in a chronologically organized six-volume series edited by Heidi Morrison and Stephanie Olsen. The Modern Age volume, like the rest of Cultural History of Youth series, pushes back against historians’ conventional reliance on nation-based frameworks and against scholarly approaches that focus primarily on Europe and North America.

Writing global histories of youth, as this volume seeks to do, is a geopolitical project; we seek to acknowledge, interrogate, and challenge the unequal power relations that shape both the lives of young people and the production of academic knowledge about them. With funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and cooperation from Bloomsbury, we have been able to publish an open-access version of the text – an undertaking which we hope will make our authors’ findings more accessible to interested readers from around the world.

A Cultural History of Youth in the Modern Age situates the twenty-first-century issues investigated by social scientists and child and youth studies scholars in a longer historical context. Foregrounding the voices and experiences of individual young people, this thematically organized volume brings together cutting-edge research on subjects including leisure, work, education, sexuality, and war. It is also a testament to the value of scholarly collaboration across institutional, linguistic, and national boundaries.

Q: What made you initiate this volume?

As we note in our Introduction, ‘youth needs to be taken seriously by all historians of the modern age’. In undertaking this project, we aimed to produce a new history of youth that spoke to the burgeoning field of youth scholarship and addressed the big themes of modern history. The history of youth is a global story which tells us a great deal about power, difference and shifting social demarcations. In telling that story, we wanted to move beyond outdated ‘West-and the-rest’ models to tackle head-on a commonplace failing of global histories, namely a tendency to address structures rather than actors. In our book the global is also granular. The questioning of boundaries was also on our minds. The volume looks beyond the confines of the nation-state, and we go well beyond 1968, a year that has commonly served as the focal (and terminus) point for youth’s appearance on a global stage.

Young people have been forceful social actors historically, but they have also been acted upon. Situated in the vanguard of historical change, young people have in many senses embodied the contradictions of modernity. In undertaking this volume, we wished to explore this tension, and to question the implicitly celebratory tone in much scholarship on youth, which notes acts of defiance, but much less often embraces complicity in acts of violence and discrimination. Doing justice to the rich history of youth globally required us to follow the lights as well as to look into the shadows.

Three short excerpts from the book:

From the Introduction:

Together, the chapters in this volume make the case that youth needs to be taken seriously by all historians of the modern age. As the anthropologists Jean and John Comaroff have written, youth are the “historical offspring of modernity”: as flesh-and-blood beings and powerful symbols, they “embody the sharpening contradictions of the contemporary world in especially acute form” (2005: 19; 21). Paying closer attention to age in general and to youth in particular makes it clear that young people have been at the forefront of many of the major processes and events that shaped human history between 1920 and 2020.

Caught between the culturally defined life stages of childhood and adulthood, modern youth have been studied and pathologized by new classes of experts; willing participants and tragic casualties in times of war; celebrated and mobilized by mass movements on the extreme left and right; and targeted as consumers and future citizens by multinational corporations and imperial/national states.

Variously the first to benefit and the first to suffer from the shifts and contractions of global capitalism, young people continue to be both exploited workers and cutting-edge producers of cultural and technological innovation. Punctuated by excitement, pleasure, hope, disappointment, and anger, the history of youth in the modern age transcends national boundaries. It is a global story which, if approached with creativity and care, has the potential to open up vital new questions about power, difference, and scale.

***

From Chapter 10 "Towards a Global History" by Kristine Alexander and Simon Sleight:

Global histories of youth, we contend, need to foreground the aspirations, sensibilities, and experiences of young people, who—mobilized by empires, nation-states, political parties, corporations, and kin for ideological, biopolitical, and profit-making purposes—variously (and at different times) pushed against and worked within the structural constraints that shaped their lives.

Violence, friction, obedience, and consent are all important forces in the history of modern youth, and this book traces how in bedrooms, laneways, shopping malls, classrooms, battlefields, farmers’ fields, and welfare and colonizing institutions, young people moved between the socially constructed life stages of “childhood” and “adulthood” by claiming, naming, and altering their identities and surroundings.

Throughout the past century, youth on the move and their counterparts who stayed put shaped and were shaped by a broad range of global forces including imperialism, war, migration, decolonization, deindustrialization, neoliberalism, and—most recently—the Covid-19 pandemic.

***

From Chapter 3 "Education and Work" by Abosede George:

Following Mamadou Diouf (2003), I argue that the twentieth century witnessed the revaluation of youth from being seen as assets of the nation to burdens on the state. Whereas in the early to mid-twentieth century, young people were valued as important to the economic ambitions of their states, by the end of the century national economies around the world had been restructured in ways that positioned young people and their needs as antagonistic to the wealth accumulation of states.

This was a dark play on the career of Viviana Zelizer’s “priceless child” (Zelizer 1985). Sharp pivots in how youth was economically valued had impacts on social investments in education and on how young people would engage with, or disengage from, formal education systems. Not only did reversals in the economic valuation of youth occur across the twentieth century, but the reversals befell different parts of the world at different points in time, starting with the “developing” world and spreading to more industrialized countries as they slid into the post-industrial era.

This revaluation simultaneously intensified and weakened the relationship between education and work, as well as the significance of education to young people who observed the ties between educational requirements and work becoming more situational than fixed. In the face of diminishing access to real work for youth globally, and widening divides between the interests of youth and state bodies, the latter decades of the twentieth century found growing numbers of young people pursuing non-normative labor practices, such as self-marketing via social media or pursuing irregular transnational migration, in order to experience the work-derived sense of personal value that had been reliably available to earlier generations (Dunn 2015; Migration Data Portal 2020).