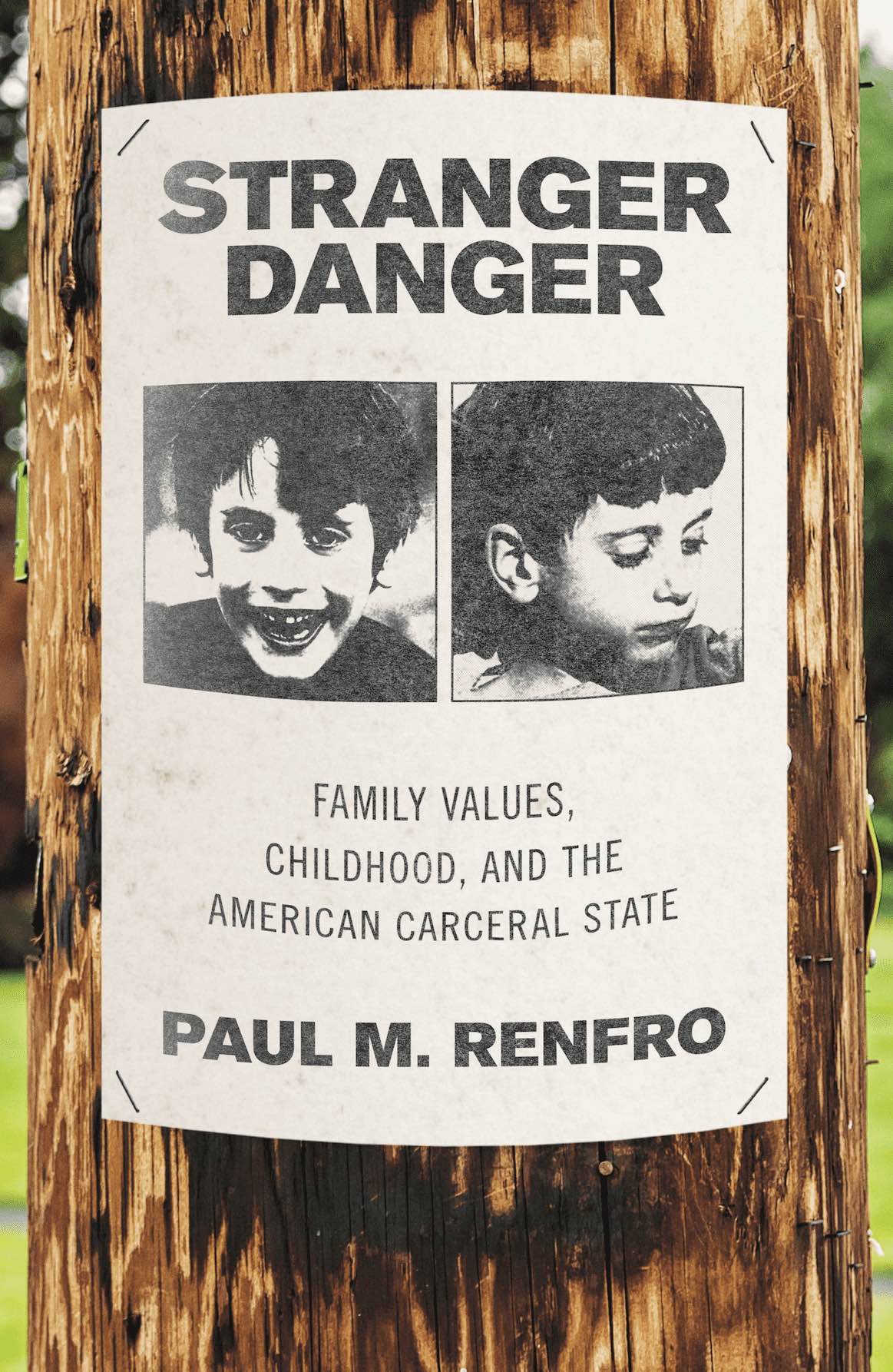

Interview with Paul Renfro about his book, Stranger Danger: Family Values, Childhood and the American Carceral State

Our member, Paul Renfro (Florida State University, United States) talks about his new book, Stranger Danger: Family Values, Childhood, and the American Carceral State (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Q: What is this book about?

Beginning with Etan Patz's disappearance in Manhattan in 1979, a spate of high-profile cases of missing and murdered children stoked anxieties about the threats of child kidnapping and exploitation in the United States. Publicized through an emerging twenty-four-hour news cycle, these cases supplied evidence of what some commentators dubbed "a national epidemic" of child abductions committed by "strangers."

Stranger Danger narrates how the bereaved parents of missing and slain children turned their grief into a mass movement and, alongside journalists and policymakers from both major political parties, propelled a moral panic. Leveraging larger cultural fears concerning familial and national decline, these child safety crusaders warned Americans of a supposedly widespread and worsening child kidnapping threat, erroneously claiming that as many as fifty thousand American children fell victim to stranger abductions annually. The actual figure was (and remains) around one hundred, and kidnappings perpetrated by family members and acquaintances occur far more frequently.

Yet such exaggerated statistics—and the emotionally resonant images and narratives deployed behind them—led to the creation of new legal and cultural instruments designed to keep children safe and to punish the "strangers" who ostensibly wished them harm. Ranging from extensive child fingerprinting drives to the milk carton campaign, from the AMBER Alerts that periodically rattle Americans' smart phones to the nation's sprawling system of sex offender registration, these instruments have widened the reach of the carceral state and intensified surveillance practices focused on children.

Stranger Danger reveals the transformative power of this moral panic on American politics and culture, showing how ideas and images of endangered childhood helped build a more punitive American state.

Q: What made you write this book?

While pursuing my PhD at the University of Iowa, I learned about eight-year-old Elizabeth Collins and ten-year-old Lyric Cook-Morrissey, cousins who mysteriously vanished while cycling in the northeastern Iowa town of Evansdale. As an outsider (coming from Texas), I was struck by the ways in which Iowans connected the Collins and Cook-Morrissey cases to the disappearances of two Des Moines-area paperboys (Johnny Gosch and Eugene Wade Martin) some three decades earlier. Locals—both in the twenty-first century and in the 1980s—conceived of Iowa as a “safe” and “innocent” place that should remain insulated from such tragedies. The paperboy disappearances, especially, shattered the “It can’t happen here” myth, in the words of one commentator. Intrigued, I began researching the phenomenon of child kidnapping in the United States, namely the panic over “stranger danger” in the late twentieth century and its effects on American political culture and the criminal legal system.

Excerpt from the book:

The Wetterlings had enjoyed their Sunday. It was October 22, 1989, and the kids had the day off from school the following day. The weather was unseasonably warm, with temperatures reaching the seventies, a good ten to fifteen degrees warmer than the average October high for central Minnesota. That morning, Jerry Wetterling had gone fishing with his son Jacob, an effervescent, handsome, and bright eleven- year- old. Jerry and Jacob then returned to their home in St. Joseph, a fifteen- to twenty-minute drive from the city of St. Cloud. They joined the rest of the family, wife and mother Patty and the three other Wetterling children—thirteen-year- old Amy, ten-year-old Trevor, and eight-year-old Carmen—to watch the Minnesota Vikings defeat the Detroit Lions, twenty to seven, at the Silverdome. After the game, the Wetterlings visited an indoor ice skating rink, and that evening, Jerry and Patty left for a dinner party some twenty miles from St. Joseph. Their eldest child Amy was visiting a friend’s house, while the other Wetterling kids stayed home, along with Jacob’s best friend Aaron Larson, also eleven years old. Jacob, Trevor, and Aaron eventually decided to ride their bikes and scooter (Aaron’s preferred mode of transportation) to the Tom Thumb grocery store, about a mile and a half from the Wetterling residence, to rent a VHS copy of the 1988 slapstick comedy The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad! Trevor called his mother Patty to ask if he, Jacob, and Aaron could go to the Tom Thumb, but she turned him down, insisting it was too dark outside. After some prodding, however, Jerry assented. Jacob arranged for a babysitter to look after his sister Carmen, and he left for the store with his brother and best friend.

The boys made their way to the Tom Thumb at a leisurely pace, at times riding their bikes and scooter, and at other times walking. The Wetterling house, on Kiwi Court, sat at the southern edge of St. Joseph. A two-way, north-to-south road flanked by cornfields, trees, and a smattering of homes connected the Wetterling residence to downtown St. Joseph. Jacob, Trevor, and Aaron traveled along this road toward the Tom Thumb, arriving at the store around nine o’clock. After successfully renting The Naked Gun, the boys began the trek back to Kiwi Court to watch the movie.

Well into their return trip—close to the Wetterling home, yet far from the lights of the St. Joseph retail district—they were accosted by a masked assailant, later identified as twenty-six-year-old Danny James Heinrich. Claiming he had a gun, Heinrich asked the boys their ages. After learning Trevor’s age, the masked man ordered the ten-year-old to run into the woods, lest he be shot. Aaron then told Heinrich that he was eleven, after which the armed man groped him. Finally, it was Jacob’s turn. After learning Jacob’s age, Heinrich instructed Aaron to run away without looking back. The assailant then took Jacob, handcuffed him behind his back, and drove him out of St. Joseph, listening to the police scanner to ensure that he could make a safe getaway. “What did I do wrong?” Jacob asked Heinrich as he transported the boy to Paynesville, about forty minutes from St. Joseph. Once there, Heinrich stopped in a field by a grove. He uncuffed Jacob and molested him, after which the boy asked if he would be returned home. Heinrich told Jacob, “I can’t take you all the way home,” causing the eleven-year-old to cry. Soon thereafter, a police cruiser, sirens blaring and lights flashing, flew down an adjacent road. Panic-stricken, Heinrich instructed Jacob to turn around; he loaded his revolver, pressed it to the back of Jacob’s head, and shot him twice, killing him. The Wetterlings would not learn their son’s fate until 2016, when Heinrich confessed.

By the time of Wetterling’s abduction and murder in October 1989, the missing child panic had already sparked a significant public, legislative, and business sector response and prompted a minor backlash against scaring children with “stranger danger” narratives. Despite attempts by some journalists and child welfare activists to debunk the exaggerated statistics animating the child protection scare, the logic of stranger danger remained firmly entrenched in 1989 and persisted into the nineties and the twenty-first century. Child safety mechanisms implemented during the presidential administration of Bill Clinton hinged upon this logic and the image of endangered childhood at its heart. Often inscribed with the names of photogenic (white) child-victims, these legal instruments (commonly known as “memorial laws”) flowed from a growing federal emphasis on protecting young Americans while punishing those who wished them harm. Among others, these federal instruments included the Jacob Wetterling Crimes against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act and the “three strikes, and you’re out” provision—both contained in the controversial 1994 crime bill—and the 1996 amendments to the Wetterling Act, known as Megan’s Law. Such laws spotlighted the moral threats ostensibly facing young Americans and identified incarceration, surveillance, control, and shame as the proper means by which to mitigate these threats. The Wetterling Act, three strikes, and Megan’s Law bolstered federal support for the mythology of stranger danger while expanding a carceral net that served to disproportionately ensnare LGBTQ Americans and people of color. Building on the developments of the 1980s, these mechanisms shored up the child safety regime and its increasingly punitive cast, enabling its continued expansion in the twenty-first century.