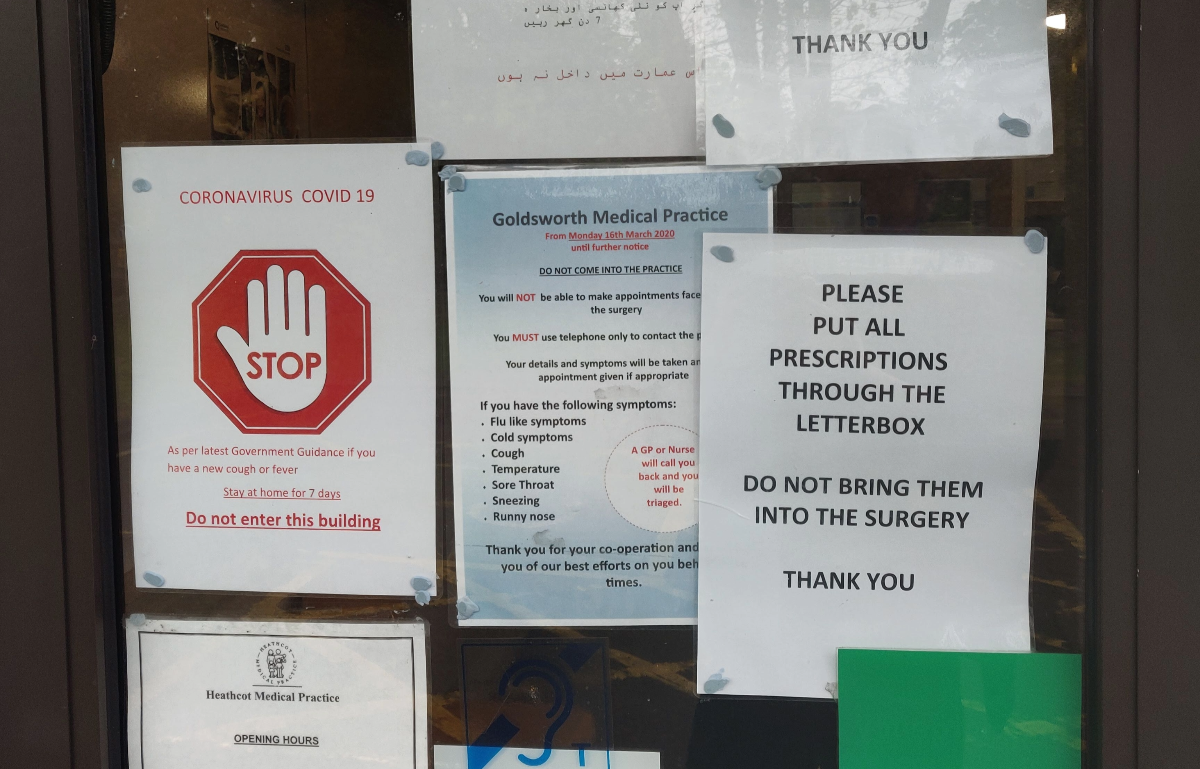

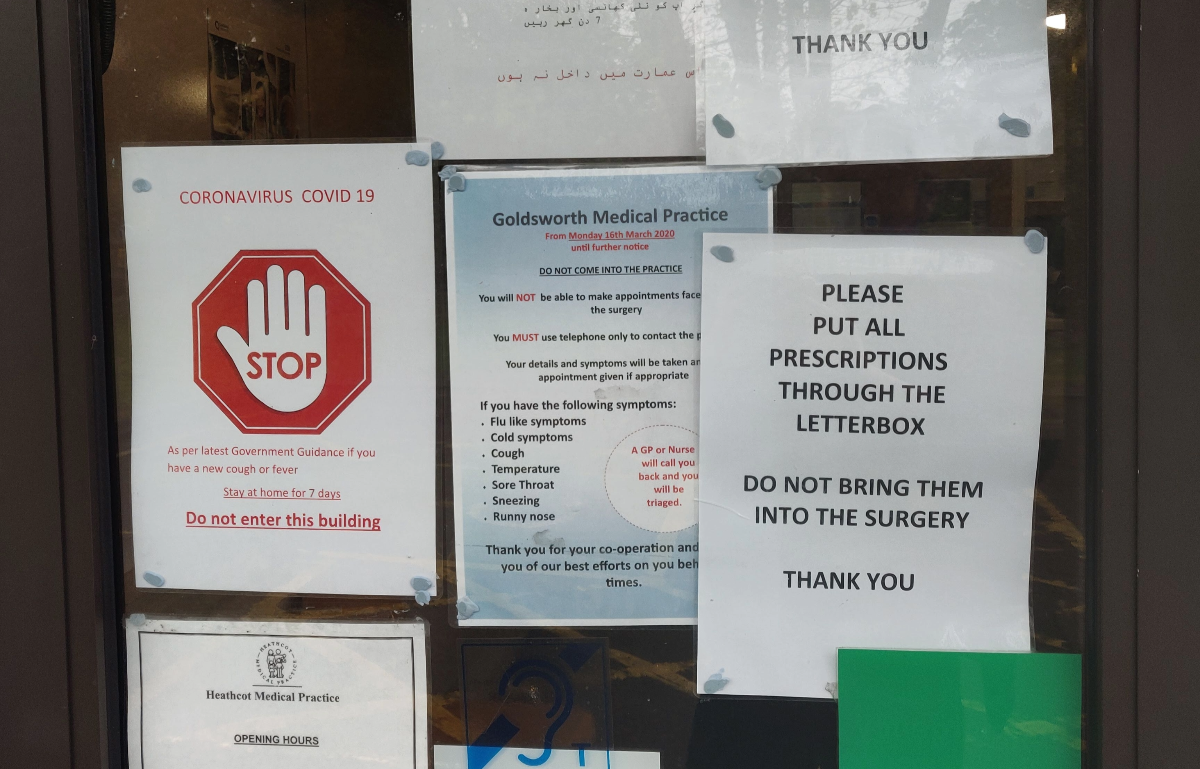

Image of COVID-19 signs at a pharmacy

The COVID-19 pandemic radically changed the way citizens and politicians approach the daily operations of government. The usual demand for effective and efficient policymaking was coupled with the need to manage an unprecedented crisis that had severe implications on our lives and how we lived them. To mitigate such uncertainty, politicians and the public turned to experts. Experts were seen as the sole actors that could provide some clarity on the important questions of the day: how severe and dangerous is this pandemic? How can we protect ourselves?

Subsequently, experts became central to managing the pandemic. Given this, we asked around 5,000 people in Germany, Greece, Sweden and the UK how their trust towards experts developed during the pandemic and during crises at large.

Trust in experts

Analysing the data we gathered from a public opinion survey in four European democracies we found that, during the pandemic’s first months, citizens were more trusting of policies coming directly from experts rather than elected politicians. Interestingly, this was the case in all four countries, despite their differences in handling the pandemic.

Experts remained the preferred source of policies in countries in which the public traditionally shows high levels of trust toward the government, that is in Sweden and Germany, and in countries where this is not the case, meaning in the UK and Greece. Equally, the public trusted experts more than politicians independently of whether it was accustomed to expert involvement in decision-making. Indeed, in Germany, the UK and Sweden experts are usually part of the debate on public policies, while this is (or used to be) far from the case in Greece. Nevertheless, in all four countries experts were more trusted compared to politicians.

Does expert involvement = better policy outcomes?

Politicians opted to trust experts and seek their advice, believing that this would lead to more efficient policies. In this sense, politicians saw experts’ input as the sole way to manage what seemed as a rather novel and enormous problem. For the public it was the symbolic significance of expert authority that led to such high trust levels.

In all four countries, the majority of people surveyed associated experts with better policy outcomes. Interestingly, they continued trusting experts even when their suggested policies did not manage to contain the virus. For example, Sweden and the UK chose to initially follow expert advice that advocated a less pre-cautionary approach. Consequently, they experienced high mortality rates compared to the rest of Europe. Despite this, the public’s trust towards experts remained higher compared to politicians. In this sense, it was the perception of competence rather than the optimal results that mainly drove citizens’ trust towards experts.

The future of expert involvement

Politicians in Western liberal democracies will be called to deal with severe crises in the future, while they will also have to build resilient mechanisms that allow them to manage such emergencies efficiently. To make things even more challenging, they are called to do so while facing declining public trust and growing contestation by anti-establishment movements.

In this context, our findings show that governments can achieve more efficient policy outcomes when making good use of experts. Consulting experts can not only improve policy making but also entails positive effects in terms of citizens' trust. It can also foster greater compliance with policy measures. It follows that governments may be able to reap substantial trust benefits by emphasising the role and contribution of experts in their crisis management efforts. To do so, they need to constructively embed experts' input in government policy by putting in place processes and platforms of co-creation. Only then will experts be in a position to fully support and publicly advocate government policies without jeopardising their own credibility and authority.