It gets better after A-levels: Doctor Faustus, Tracey Emin, and why I study English at Queen Mary

by Saramarie Harvey, BA English

Studying English as an undergraduate is about unlearning the essay writing conventions taught at school. You learn to engage with your work more critically, and it’s exciting. It prompts thought-provoking seminar conversations and independent learning.

During my A-level studies, I found myself gravitating towards creating artwork and writing essays on subject matter relevant to my identity. Studying the Tudors and reading Chaucer did not interest me so much as learning about the gradual collapse of the British Empire, responding to the post-9/11 immigrant experience, and sewing tongue-in-cheek feminist commentary into Tracey Emin-inspired tapestries.

Growing up as a young, Black British woman amid tumultuous UK politics, I knew I wanted identity politics – especially race and gender – to be at the core of my undergraduate research. I wanted to defy the patriotism we were spoon-fed through the British school curriculum. I wanted to appreciate the global narratives which inform the multitude of intermingling cultures in present-day London, rather than believing that ‘Other’ narratives are inferior to the British perspective.

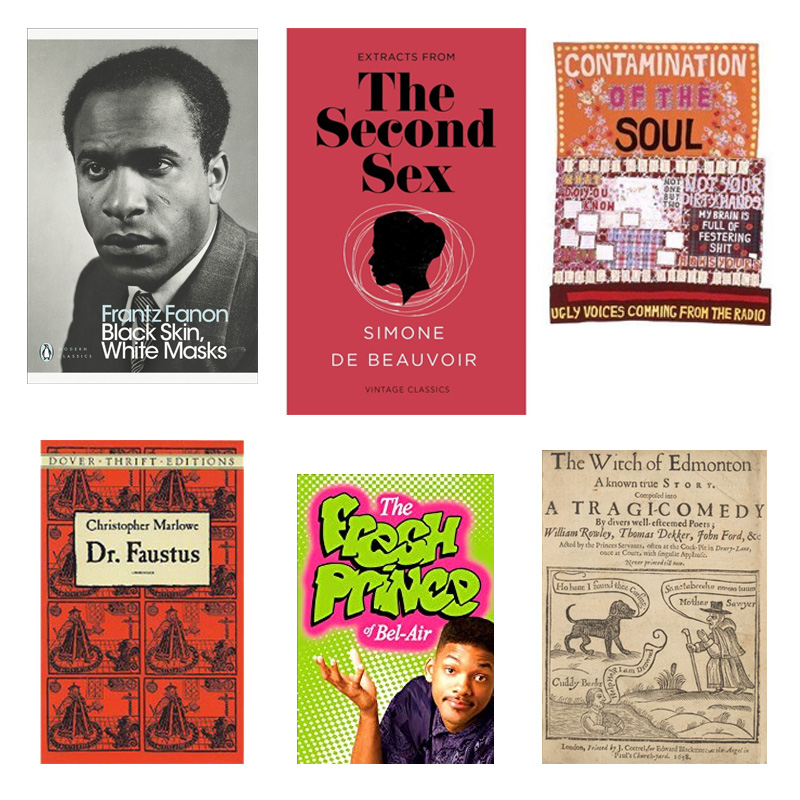

I was interested in going to a university which would facilitate my ambition to focus on contemporary and postcolonial studies. As one of the few Russell Group universities breaking away from the constraints of strictly teaching traditional modules, Queen Mary’s English course aligned with my interests. The catalogue of modules is endless, many of them consolidating my affinity for topics I already loved. Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex acquainted me with thinking critically about gender, while Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks taught me about the psychological effects of creating racial differences.

Studying English at university has also introduced me to topics and critical theories I had not encountered in literature before. I love watching sitcoms like The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and enjoy making my friends laugh, but it was not until I came to university that I realised that comedy and satire constitute as discourse for literary discussions.

I was still met with a week of Chaucer during my first year and occasional references to the Elizabethan period in a second year Renaissance module. I did not mind. The medieval and early modern classes gave me the scope of knowledge that should be expected from a degree. In fact, I miss contributing both banter and intellect to seminars about The Wife of Bath and The Witch of Edmonton. Studying medieval and early modern literature at university has been more dynamic than at A-level: with each week dedicated to focusing on a different text, it was far less repetitive. It became rewarding to revisit the time periods that would make me yawn, and I found that the Tudors is not all about the monarchy’s marital dramas and the murky River Thames. It can be the supernatural in Doctor Faustus, or the scientific discoveries of Andreas Vesalius.

Rather than struggling to remember Shakespeare and forcing a rigid structure of assessment objectives, university stops literary criticism from being a memory test. It allows actual literary criticism with a solid argument to flow from the mind and through the ink of the pen. Studying English as an undergraduate is about unlearning the essay writing conventions taught at school. You learn to engage with your work more critically, and it’s exciting. It prompts thought-provoking seminar conversations and independent learning.

The teaching is far superior to being coddled into simply believing that Britain is the hero of the World Wars – whilst colonial support is omitted from the textbooks. At A-level, information is handed to you to memorise without much thought. At university, seminars are stimulating, and independent reading encourages you to form opinions and a line of argument, rather than just analysing literary techniques. I suddenly started enjoying modules I did not expect to because my degree encouraged me to write differently. English Literature at Queen Mary is captivating. It is everything you could think of and already love, and everything you haven’t even thought of yet.