A window into convent life in early modern Europe

In 1598, the first English convent was established in Brussels by a group of women who chose to flee an increasingly anti-Catholic England to follow the religious life. In the two centuries that followed, another 20 enclosed convents were opened across Flanders and France.

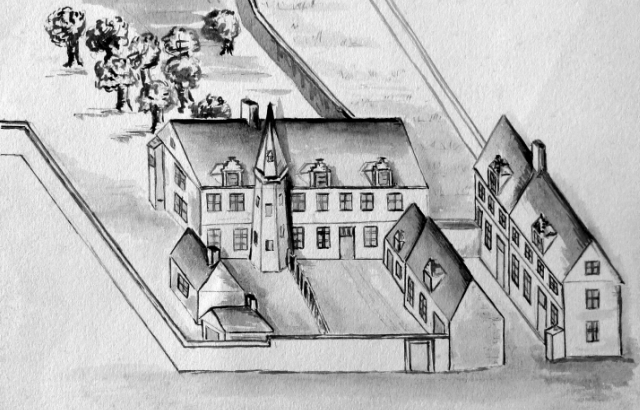

The English Convent in 1629

A new book by historian Dr Caroline Bowden from Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) publishes for the first time the chronicles written by the Augustinian nuns in Bruges. The book vividly depicts life in an English convent in exile.

In theory, the nuns were cut off from the outside world. In practice, says Dr Bowden, they were deeply connected to their local communities and to wider religious networks in Europe. The Chronicles of Nazareth (the English Convent)describe a group of extraordinary women - strongly influenced by continental intellectual culture, and who in turn contributed to a developing English Catholic identity, shaped by their experiences in exile.

Living in exile, members of the convent were well-aware of their importance to the survival of English Catholicism for women, according to Dr Bowden. “Keeping full records served to maintain a reputation which would attract influential and well-heeled benefactors and suitably-qualified members.”

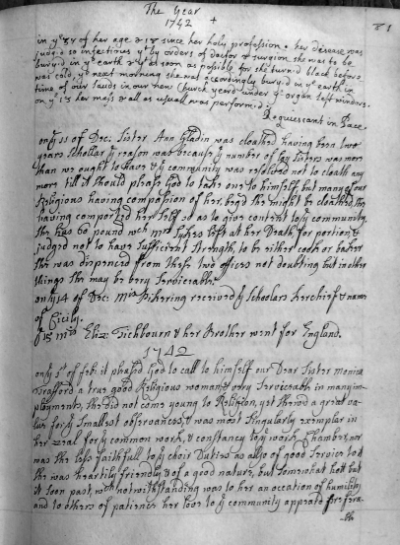

Opening of the manuscript copy of Volume I of the Chronicles.

Lives in exile

Dr Bowden says the Bruges Chronicles, published for the first time in this volume, introduce the reader to members at every level, from impressive community leaders, to domineering priests, to candidates who failed to live up to expectations and were tactfully nudged out. It also gives space to those who lived out their lives in quiet contemplation.

She says: “We meet Prioresses who take on major challenges in fund-raising to pay for building projects, manage disagreements over spiritual direction and adjust to new relationships with secular authorities, the impact of the Enlightenment, and finally war. There are some intense personal dramas that unfold alongside nuns who followed the monastic rule to the letter and served the community faithfully over many years.”

The first two volumes of the Chronicles take account of life in the convent until the 1793, when the survival of the community was seriously threated by the invasion of French troops. The membership of the English Convents was first explored by the Who Were the Nuns? project, funded by Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

A profile of Mother Augustina More, Prioress 1766-1807

Prioresses at Bruges were elected for life using secret ballot. Augustina More was the last descendant linking the convent directly to St Thomas More, a significant connection for the community. She had only been professed for thirteen years when elected Prioress, and her qualities were respected both inside and outside the walls of the enclosure.

This is reflected in the size of the community she led. Candidates were not attracted to cloisters where leadership was considered weak. Mother More reformed community rules and she led them through the challenging time of reforms, based on Enlightenment principles. As other contemplative communities were shut down, individual members, both men and women, were taken into the convent and sheltered until they were able to make plans.

A page from Volume II of the Chronicles showing the change of hand between writers

For Mother More, the last years in volume two are filled with the appalling uncertainties created by events in France. We see how the leaders of the convent were trying to decide how to deal with the valuables, who could be trusted, how to get the best deal, how to look after the elderly and the sick. She had boarders from the West Indies as well as Europe in the community. One of them (a small boy) had a black nurse with him which would have been an unusual sight in those days.

Dealing with a scandal: Sister Perpetua Errington (1681-1739)

Baptised Dorothy in a well-known Northumbrian family, she professed in 1681, choosing the name Perpetua. She was described as frequenting the parlour, where she was ostensibly talking to soldiers of William III’s army with the intention of converting them to Catholicism. However, on the night of 1696 she left the convent in her nightgown with John Grant. She was not missed until the following day because her attendance at divine office was so irregular.

When Reverend Mother using her “emperor” key opened her cell they found her habit and veil abandoned. She married John Grant in Sluys, and was found there living in poverty by a family member. She refused to return to the convent and left for Scotland. Five years later word came from her brother that she had died.

Later the nuns learned that in fact the woman who had come to his house and died there was an imposter suffering from syphilis. Dorothy was still alive and had contacted a bishop in Scotland saying that she wished to return to the convent. The nuns offered to pay the expenses of her journey, but nothing more was heard for several months. They had given up hope when she appeared in 1707 (eleven years after she left) accompanied by a Benedictine monk. She explained that her return was prompted by the death of her husband and her brother John had paid for her travel.

She was accepted by the community provided she agreed to a trial separation of a month and to follow the Rule closely in future. The Sunday following, she received her habit and prostrate before the community, begged pardon. The Chronicler writes “She was received among us as a reunited member of our community, with the kiss of peace from everyone... We hope God’s infinite mercy will complete the work he has so happily begun.”

More information

- Dr Caroline Bowden is a Senior Research Fellow at QMUL's School of History

- Find out more about studying history at QMUL

Related items

31 October 2024

For media information, contact: