Bank of England ledgers reveal failure of World War One loan scheme

The British government’s initial efforts to pay for World War One through loans from the public was a spectacular failure, according to a new study using restricted Bank of England ledgers. The research reveals that the War Loan scheme failed to such an extent that the Bank of England had to secretly fund half the shortfall.

Sworn statement that all £350 million had been sold to the public © National Archives

The results are early findings from a major project on World War One finance, co-led by researchers at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) and the Bank of England.

As part of the project the research team was granted exclusive access to ledgers in the Bank of England which show that the government’s first War Loan scheme of 1914 raised less than a third of its £350 million target. The £91 million that was raised publicly came mostly from a tiny group of wealthy financiers, companies, and private individuals.

QMUL researcher Norma Cohen says: “The fund raising effort was such a failure that the establishment felt compelled to cover it up. The truth would have led to a collapse in the price of outstanding war loans which would have endangered future capital raising. Had it come to light, it would have been a propaganda coup for the Germans – the great patriotic project to pay for the war was mostly a myth."

Secrecy

The government and the Bank of England moved quickly and secretly to plug the gap. The Bank’s Chief Cashier Sir Gordon Nairn and his Deputy Ernest Harvey purchased the outstanding loans in their own names with the bonds then held by the Bank on its balance sheet. To hide the fact that the Bank was forced to step in, the bonds were classified as holdings of ‘Other Securities’ in the Bank’s balance sheet, rather than as holdings of government securities. To compound the secrecy, Sir Gordon later formally swore a statement that all £350 million had been sold to the public.

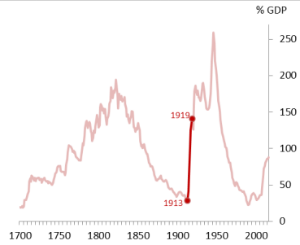

UK national debt

This is the first time that the full scope of government efforts to hide the scale of the War Loan failure has been revealed. This failure was to haunt senior ministers for the duration of the war as it struggled to raise the capital needed by Britain and its allies to defeat Germany and dictate peace terms.

The failure of the scheme was in stark contrast to the public’s perception of the War Loan effort. The government led a propaganda effort to persuade the public that the scheme had been an overwhelming success. The Financial Times reported on 23 November 1914 that the scheme was “over-subscribed by £250 million…and still the applications are pouring in”.

War-time fundraising

Alastair Owens, Professor of historical geography at QMUL and Principal Investigator on the project says the failure of the scheme had a significant impact on Britain’s approach to war-time fundraising.

“Faced with the possibility of an Allied defeat, Britain showed a willingness to abandon the free-trade and laissez-fair principles that were the hallmarks of Liberal and Conservative governments in the decades before 1914,” says Professor Owens.

Evidence from the sample of early investors in the War Loan shows that ‘sacrifice’ and patriotism alone were not sufficient to attract the required funds. Subsequent war financings would offer investors even higher premiums and previously unthinkable tax breaks in exchange for capital. This includes the mammoth War Loan of 1917 which raised £2.1 billion with a hefty return of 5.4 per cent.

But after the war, according to Norma Cohen, the battle began over how that debt burden should be shared.

Percentage of households purchasing War Loans by region

“As the war unfolded, ministers were pilloried for rewarding investors far too generously for surrendering capital which should have been sacrificed gladly as a matter of patriotic principle. In the 1920s, as debt service rose to nearly 40 per cent of tax receipts, investors were cast as profiteers, idly collecting rents on War Loans while others toiled,” said Ms Cohen.

- The researchers are grateful to staff at the National Archives for allowing the publication of images used in this story.

Sample investors

Julia Caroline Mary Mocatta ---

Ms Mocatta was one of the early investors in War Loan, purchasing £300 in stock on 28 December 1914 through a plan to pay on instalments known as ‘scrip’. On 1 October 1915, she took the opportunity to convert into the more generous 4-1/2 per cent War Loan.

The ledgers identify her occupation as ‘Spinster’ reflecting the prevailing practice of describing women only by their relationship to a man. However, the 1911 Census reveals she was much more than that; she is a nurse at a home in Grosvenor Place, Southampton, the same address as is listed in the ledger. According to King’s College London archives, Ms Mocatta, born in Bispham, Lancashire, was the daughter of a vicar who died when she was only 17. She had an accomplished career as a nurse, training first at University College Hospital in London and then at Charing Cross Hospital.

Average value of War Loan holdings by region

By the time she became Matron at Royal Hampshire County Hospital in 1895, she was earning an annual salary of £100, well above the national median and placing her firmly among Britain’s expanding middle classes. By the time war broke out in 1914, she was 55 years old – old enough to have accumulated a tidy savings pot – and had already developed a nursing course for women who had not had any formal training. She was active in Church circles and was honorary treasurer of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. She died in 1932, leaving an estate valued at over £21,000.

Sir Iain Colquhoun-of-Luss ---

Sir Iain was a Scottish baronet and one of a group of four well-to-do young men who clubbed together to invest in War Loan in December 1914, buying £1,000 of the 3-1/2 per cent issue. Half was sold in October 1915, but the remainder was converted into the 4-1/2 per cent War Loan.

He succeeded his father to become the 7th Baronet of Luss, a title that goes back to the early 15th century. Sir Iain was an officer in the 1st Battalion Scots Guards serving on the Western Front, and was wounded, awarded a Distinguished Service Order and suffered a court martial. The details and photo can be found here. After the informal Christmas truce of 1914, British generals decreed that such an event must not happen again. However, at Christmas, 1915, during a temporary lull, Sir Iain agreed to a German request that each should have three-quarters of an hour to collect and bury their dead.

“The Germans then started burying their dead and we did the same,” he wrote in his diary. “This was finished in ½ hrs time. Our men and the Germans then talked and exchanged cigars, cigarettes etc. for ¼ of an hour and when the time was up I blew a whistle and both sides returned to their trenches.” Sir Ian went on to become engaged in civic and military activities after the War and in 1931, was among the founders of the National Trust for Scotland. He died in 1948 and the age of 61.

More information

- The project is co-led by Dr Daniel Todman from QMUL's School of History and Professor Alastair Owens from QMUL's School of Geography

- Learn more about studying Geography at QMUL

- Learn more about studying History at QMUL

Related items

10 December 2024

10 December 2024

For media information, contact: