Like father like son? How we balance work and family life may be learned from our parents

The extent to which we prioritise work versus family life may be shaped by our childhood experiences in the family home, according to a study co-authored by Dr Ioana Lupu from Queen Mary University of London (QMUL).

Previous work-life balance research has focused more on the organisational context or on individual psychological traits to explain work and career decisions. However, this new study, published in Human Relations, highlights the important role of our personal history and what we subconsciously learn from our parents.

"We are not blank slates when we join the workforce -- many of our attitudes are already deeply engrained from childhood," according to co-author by Dr Ioana Lupu (School of Business and Management).

The study argues that our beliefs and expectations about the right balance between work and family are often formed and shaped in the earliest part of our lives. One of the most powerful and enduring influences on our thinking may come from watching our parents.

Four categories

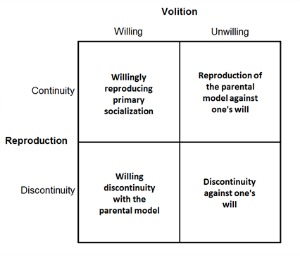

The research is based on 148 interviews with 78 male and female employees from legal and accounting firms. Interviewees were sorted into four categories by the researchers: (1) willingly reproducing parental model; (2) reproducing the parental model against one's will; (3) willingly distancing from the parental model; (4) and distancing from the parental model against one's will.

Matrix of situations linking anticipatory and professional socialisation

Male participant in the study: "I've always had a very strong work ethic drilled into me anyway, again by my parents, my family. So, I never needed anyone looking over my shoulder or giving me a kick up the backside and telling me I needed to do something -- I'd get on and I'd do it. So, I found the environment [of the accountancy firm] in general one that suited me quite well." (David, Partner, accountancy firm, two children).

Women are more conflicted

Women on the other hand were much more conflicted -- they reported feeling torn in two different directions. Women who had stay-at-home mothers "work like their fathers but want to parent like their mothers," says Dr Lupu.

Female participant in the study: "My mum raised us...she was always at home and to some extent I feel guilty for not giving my children the same because I feel she raised me well and she had control over the situation. I'm not there every day ... and I feel like I've failed them in a way because I leave them with somebody else. I sometimes think maybe I should be at home with them until they are a bit older." (Eva, Director, accountancy firm, two children).

Women who had working mothers are not necessarily always in a better position because they were marked by the absence of their mothers. A female participant in the study remembers vividly, many years later how her mother was absent whereas other children's mothers were waiting at the school gates.

Female participant in the study: "I remember being picked up by a child-minder, and if I was ill, I'd be outsourced to whoever happened to be available at the time . . . I hated it, I hated it, because I felt like I just wanted to be with my mum and dad. My mum never picked me up from school when I was at primary school, and then everybody else's mums would be stood there at the gate . . . And it's only now that I've started re-thinking about that and thinking, well isn't that going to be the same for [my son] if I'm working the way I am, he's going to have somebody picking him up from school and maybe he won't like that and is that what I want for my child?" (Jane, Partner, law firm, one child and expecting another).

Negative role models

An exception was found in female participants whose stay-at-home mothers had instilled strong career aspirations into them from an early stage. In these cases, the participants' mothers sometimes set themselves up consciously as 'negative role models', encouraging their daughters not to repeat their own mistake.

Female participant in the study: "I do remember my mother always regretting she didn't have a job outside the home and that was something that influenced me and all my sisters. [...] She'd encourage us to find a career where we could work. She was quite academic herself, more educated than my father, but because of the nature of families and young children, she'd had to become this stay-at-home parent." (Monica, Director, AUDIT, one child)

"We have found that the enduring influence of upbringing goes some way towards explaining why the careers of individuals, both male and female, are differentially affected following parenthood, even when those individuals possess broadly equivalent levels of cultural capital, such as levels of education, and have hitherto pursued very similar career paths," says Dr Lupu.

She says the research raises awareness of the gap that often exists between unconscious expectations and conscious ambitions related to career and parenting.

"If individuals are to reach their full potential, they have to be aware of how the person that they are has been shaped through previous socialisation and how their own work?family decisions further reproduce the structures constraining these decisions," says Dr Lupu.

More information

- “When the past comes back to haunt you: The enduring influence of upbringing on the work–family decisions of professional parents”, by Ioana Lupu, Queen Mary University of London; Crawford Spence, University of Warwick; Laura Empson; Cass Business School, UK. Human Resources, doi: /10.1177/0018726717708247

- Dr Ioana Lupu is a Lecturer in Management Control at QMUL's School of Business and Management

- Learn more about studying Business Management at QMUL

Related items

10 December 2024

10 December 2024

For media information, contact: