Inflation will probably melt away in 2022 – central banks will do far more harm trying to tackle it

Professor Brigitte Granville from Queen Mary's School of Business and Management has written for The Conversation on banks' efforts to tackle inflation.

It remains to be seen whether the omicron variant will shift Sars-CoV-2 towards becoming manageably endemic. But as and when this happens, there will still be “long COVID” to contend with. The latest headlines about inflation – a 7% annual rise in the US and more tough talk from Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell about bringing it down – confirm that something similar is happening with the global economy: it will be shaped by the after-effects of the pandemic even when all restrictions have been lifted.

To understand how this overhang effect may play out in 2022 requires looking back at how the pandemic has affected growth and inflation. The key lies in decisions taken after the initial phase in 2020 when governments shut down large parts of their economies while compensating households and businesses for lost income to prevent an economic depression. People both saved more than usual and redirected their spending from services like eating out or travel to goods for the home – notably digital equipment for remote working and leisure.

Such goods started running out of stock and it took longer than usual for supplies to recover, not least because COVID restrictions had hit the global supply chain. The same went for other key consumer requirements such as energy: as demand for oil rebounded, the supply was constrained either by political decisions, such as the Opec+ cartel declining to raise production, or the financial fragility of US shale oil producers.

Shortages have caused inflationary pressure, which has also been aggravated by factors linked to the climate emergency. Since replacing coal with a “greener” fossil fuel in electricity generation is one of the quickest ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, there has been increased demand for natural gas. And in food markets, agricultural production has been damaged by the growing frequency of extreme weather events.

Misapprehensions about inflation

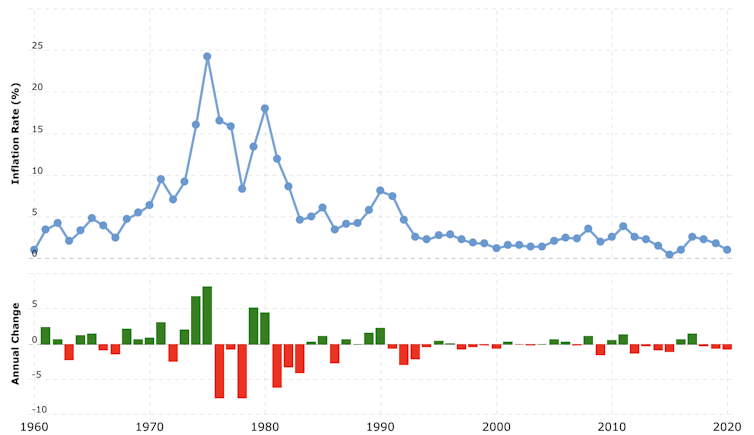

In many advanced industrial countries, headline inflation rose by the end of 2021 to its highest level in two decades: that annual rate of 7% in the US in December, and 5% in the eurozone (the two regions measure inflation in slightly different ways).

Meanwhile, the bounce in world economic growth in 2021 after the initial pandemic slump has been naturally giving way to a slower pace of growth. This is in line with more normal trends now that major economies have returned to, or are approaching, their pre-pandemic levels of output. This combination of slowing growth and rising prices – often labelled “stagflation” – is pernicious if it continues, attracting widely voiced concerns as 2021 wore on.

I would argue, however, that this threat is exaggerated. It stems to a considerable extent from a confusion between an increase in price levels and genuine inflation defined as persistent and volatile increases in the rate of price growth. This is a subject close to my heart, which I discuss in my 2013 book Remembering Inflation.

The price rises can be largely explained by this problem of suppliers being unable to provide enough goods to meet the rebound in consumer demand. And one key development which became apparent by the end of 2021 was that the supply of manufactured goods had recovered sufficiently to correct this inflationary imbalance.

UK inflation, 1960-present

China has made the running here, along with other Asian manufacturing powerhouses. In November 2021, manufacturing inventories in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan were 20%-30% higher than the previous month. More generally in December, global industrial output was 12% higher than a year earlier, having shown a 5% annual contraction as recently as September.

This suggests not only that the stagflation threat will recede, but also that a “wage-price spiral” characteristic of any serious inflationary episode, is increasingly unlikely: this is where workers are able to demand higher and higher wages to make the rising cost of living affordable, which in turn further pushes up prices.

The central bank dimension

It follows that major central banks may err in going too far in their declared intention to raise interest rates to control inflation. The Bank of England has led the way by announcing its first post-pandemic rate hike in December (from 0.1% to 0.25%).

As for America, financial markets are pricing in a first rate hike by the US Federal Reserve in March – the same month as it aims to stop buying bonds and other financial assets as part of its quantitative easing (QE) programme to prop up the economy. Even the more doveish ECB recently announced a trimming of its QE programme, though it has no plans to raise interest rates this year.

Several commentators think these moves don’t go far enough. They argue that given the persistent threat of inflation, central banks should raise rates more aggressively and offload assets bought under QE programmes – which the Fed has signalled it might start doing by the middle of this year.

The difficulty for central banks is that prices could certainly keep increasing for a while. For instance, when the omicron wave subsides, demand for services like restaurants or travel should recover. Yet rather like someone with long COVID, the supply side in many of these industries remains “scarred”: numerous service businesses closed during the pandemic – witness the shuttered retail premises on high streets – and it can take time to raise working capital and re-hire the staff required to reopen. So just like in 2020-21 as regards goods, extra demand chasing too little supply could now push up prices in services.

Though raising interest rates won’t solve this problem, it’s the potential for a resulting wage-price spiral that is worrying central banks. Numerous developed countries have already been seeing pressure on wages developing naturally from the recovery of employment, since this means employees are in higher demand. This trend is being further intensified by labour shortages, largely caused by impediments to migration such as the difficulty of applying for H1B visas to the US and the UK government’s post-Brexit strategy of reducing migrant labour inflows.

Though concerns about wage pressure are well founded, they should nevertheless be offset by an important disinflationary impulse likely in 2022. In China, the first major economy to recover from the pandemic, the authorities are now relaxing monetary and fiscal policy (government spending) to counter the ensuing slowdown. But unlike previous Chinese stimulus drives in the years between the global financial crisis and the pandemic, which largely drove global growth, this latest easing only seeks to stabilise the economy. The Chinese fear further increases in the country’s indebtedness and the associated threat to stability.

With global supply chains returning to some kind of normality and China in this cautious mode, the overall effect will probably be that inflation eases of its own accord. If so, raising rates and quickly rolling back QE will just choke off recovery at a time when many countries are barely on their feet after COVID. The next problem could well end up being slowdown or even recession.

This article was first published in The Conversation on 14th January.

Related items

29 November 2024

12 November 2024