Ukraine: world financial markets have not broken sweat since the Russian escalation – why?

Daniele Bianchi, Associate Professor of Finance at Queen Mary University of London, has written for The Conversation on how financial markets are affected by wars and other political events.

The economic consequences of armed conflicts have received widespread attention at least as far back as when John Meynard Keynes wrote about them in 1919 in relation to the first world war. Yet as the world braces for a possible war in Ukraine, we still know relatively little about the interplay between conflicts and financial markets.

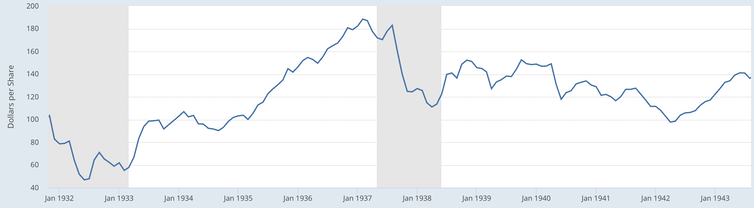

One thing we can say is that even during major armed conflicts, financial markets have often operated relatively smoothly. A clear example is the second world war. Most people would probably think there would have been a sharp dive in the stock market in September 1939 with the invasion of Poland, or after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Yet as you can see from the following chart of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, that is not what happened.

The market instead bottomed much earlier, in 1938, when Hitler annexed Austria as part of his Anschluss plan to reunite all of the German-speaking people in Europe. This was the first concrete signal of the build-up of a global war.

Until the fall of France in the spring of 1942, markets remained extremely complacent about the ongoing armed conflict. In fact, after bottoming again in 1942, the market began a bull run well before the end of the war. This possibly reflected the assumption that the Allies were starting to get their act together. With the full-force intervention of the US towards the end of that year, winning the war was starting to look like a concrete possibility.

The events of the second world war show a key characteristic of financial markets: they react abruptly only to unexpected events, while largely expected outbreaks are priced in (already factored into valuations) well in advance. So, for example, the 9/11 attack triggered a violent reaction on financial markets, but the largely anticipated military occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq were largely ignored.

This possibly relates to the very nature of financial markets. Investors hate uncertainty more than anything, and there are few situations more uncertain than the threat of a war. When an armed conflict begins, however, to some extent uncertainty resolves and capital is reallocated.

Ukraine and the markets

These observations can perhaps help to explain the complacency of international financial markets in response to Russia’s announcement that it is recognising as independent states the eastern Ukrainian territories of Donestk and Lugansk and sending in “peacekeeping” forces to help defend them from Kiev. The S&P 500, major European stock markets and the VIX (which measures of market volatility) barely moved on a daily basis in response. On the other hand, the Russian stock market index fell by about 10%.

This could mean that international capital markets have already been pricing in the risks of (a minor) conflict with Russia as part of the slide in stock prices over the past couple of months. The view could be that as serious as this escalation could be, it is unlikely to have a material impact on US, EU or UK economic fundamentals or corporate profits. If so, given the strategic importance of Russia as a net exporter of natural gas and oil, especially to the EU, this assumption might be questionable at the very least.

Meanwhile, the drop in the Russian stock market might reflect a belief that western sanctions will primarily affect the Russian economy. Of course, there is the possibility of contagion effects across countries, especially Russia’s neighbours, but these are hard to quantify as they depend on the exposure of other countries to the Russian economy.

Either way, markets have been conditioned not to overreact to largely anticipated political and geopolitical shocks. Yet bear in mind that Russian gas pipelines feed many parts of Europe. The price of natural gas in Europe has already gone up 11% since Putin’s announcement, while Brent crude oil is up by 1%.

If Russia were to shut off the gas spigot, or have its oil infrastructure damaged, we could easily see a bigger spike in the price of these resources - which would feed into already high inflation. Interruptions to the ports around the Black and Baltic seas could also exacerbate continuing disruptions to the global supply chain, which could affect both European and UK recovery from the pandemic in the short-term.

In other words, while market complacency might have a rationale, it should be taken with the proverbial grain of salt. And all this is under the assumption that an eventual escalation in Ukraine should be limited to the Donbas area. Unfortunately, this remains to be seen.

This article was first published in The Conversation on 22nd February 2022.