Monkeypox: latest data reveals how the virus has affected women and non-binary people

Dr Chloe Orkin, Professor of HIV Medicine at Queen Mary University of London and Director of the SHARE collaborative, has written for The Conversation after leading an international collaboration of clinicians to publish the first case study series of monkeypox infection during the 2022 outbreak in cisgender (cis) and transgender (trans) women and non-binary individuals assigned as female at birth.

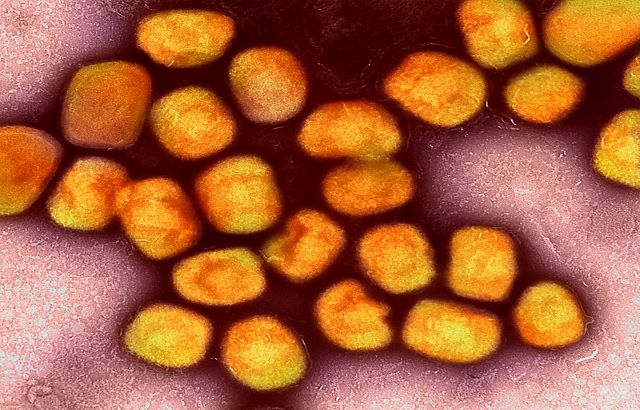

Colourised transmission electron micrograph of monkeypox virus particles (gold) cultivated and purified from cell culture. Image captured at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Maryland. Credit: NIAID

Since May 2022, a global outbreak of human monkeypox infections has been reported in over 78,000 people. So far, infections have overwhelmingly occurred in sexually active men who have sex with men.

Given the vast majority of infections have occurred in gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, most of the data we have on the global impact of monkeypox and how it transmits has been in this group. As such, we haven’t fully known how many cases of monkeypox were affecting women or non-binary people assigned female at birth – and how it’s being passed on in these groups. This is what our latest research has uncovered.

I reached out to my fellow researchers in countries seeing high numbers of monkeypox infections, asking them to collaborate in a case series looking at features of monkeypox in women. Our study included data from 15 countries, including the USA, France, Spain, Mexico, Chile and Nigeria.

Our case series included 136 people in total. Of these, 69 were cisgender women (women assigned female sex at birth who identify as female), 62 were transgender women and five were non-binary people assigned female sex at birth. We found many similarities and several differences in how monkeypox is passed on and the symptoms the disease was causing in cisgender women, transgender women and non-binary people.

Sexual transmission was suspected in around 90% of transgender women but only in 61% of cisgender women and non-binary people. Non-sexual transmission was only reported in cisgender women, and happened as a result of household contact with a person with monkeypox or an exposure at work. In some cisgender women and non-binary people, the doctors were unsure of the route of transmission.

In general, symptoms of the disease were similar to what has been described in men, with the large majority of participants reporting anal and genital rashes and sores which corresponded to the type of sex they had. The rash and sores were sometimes accompanied or preceded by fever, headache, muscle aches and sore throats. Cisgender women who acquired monkeypox non-sexually were less likely to have anal or genital rashes or sores, though symptoms were otherwise similar.

And just as we described monkeypox virus in semen in a previous study, we also found it in vaginal fluid. This makes it even more likely that monkeypox is transmitted through sexual fluids, as well as through skin-to-skin contact.

We also showed that half of transgender women who contracted monkeypox were living with HIV compared with only 6% of cisgender women. People living with HIV have been at high risk of monkeypox during the outbreak for reasons that still aren’t entirely clear and our data research continues to support this finding.

We also found that cisgender women were much more likely to be misdiagnosed and more likely to attend emergency departments with symptoms. This is why it’s so important to understand how monkeypox is transmitting in different groups and to educate doctors everywhere on what to look for.

Current situation

Since the outbreak’s apparent peak in August, monkeypox numbers appear to have fallen drastically in many countries – including France, the UK, Canada and parts of the US. For instance, 13 European countries have not reported a new monkeypox case in the last 21 days.

This seems to indicate that the public health interventions being used in many countries to combat monkeypox – such as vaccinations and encouraging people to change their sexual behaviour – appear to be working. Our data also indicates that the risk of monkeypox becoming more widespread in the population still remains low.

But while cases may be falling in many countries, they still remain high in Latin America, especially in Brazil. In west and central Africa, they’ve been battling it for 50 years. It’s of the utmost importance that these regions also have access to vaccines to prevent further spread and harm. Currently many countries have limited access to vaccines.

Our study highlights how important it is to monitor the spread of disease in groups who may not have initially been affected, especially in order to prevent further transmission and harm. Our study also highlights the importance of scientists reporting on both sex and gender identity in their research.

Until recently, studies didn’t ask people about both their sex at birth and their gender identity. Not asking these questions means we can’t improve health if we don’t even know what health problems people have, or how certain health conditions may be passed on through different parts of a population. This information is also crucial to providing better care to people, especially those who are underrepresented.

This article was first published in The Conversation on 21 November.

Related items

11 January 2024