Does the British Electorate Mind Politicians Doing God?

Philip Cowley and Alan Wager from the School of Politics at Queen Mary University of London, has written for 'Theos' where they unpack Theos’ data on the public’s views of certain religious beliefs being held by people in office.

Earlier this year, following the row over Kate Forbes’ religious views, Theos released data showing the extent to which the public felt people who held religious or other private views should be excluded from high office. For the most part, it found people censorious of those with socially conservative political views, while religious beliefs were more accepted.

But these groups may well overlap. After all, there are two paths to opposing a religious person being in power. The first is believing an Evangelical Christian or a Muslim should not be allowed to be Prime Minister or in the cabinet. The second would be to be accepting of the principle but not of the practice: being happy with an Evangelical Christian leader in theory, but not one who thinks, for example, that gay relationships are a sin.

In this blog, we probe a bit further into the data and show that opposition to certain types of religious politicians may be greater than the data first shows.

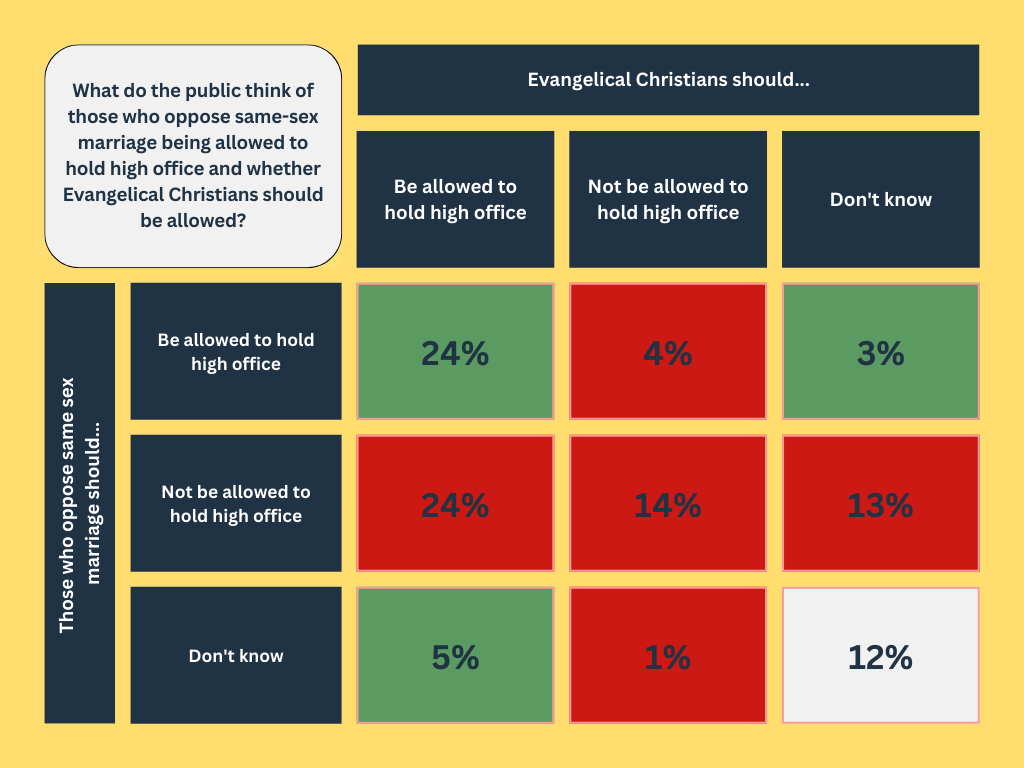

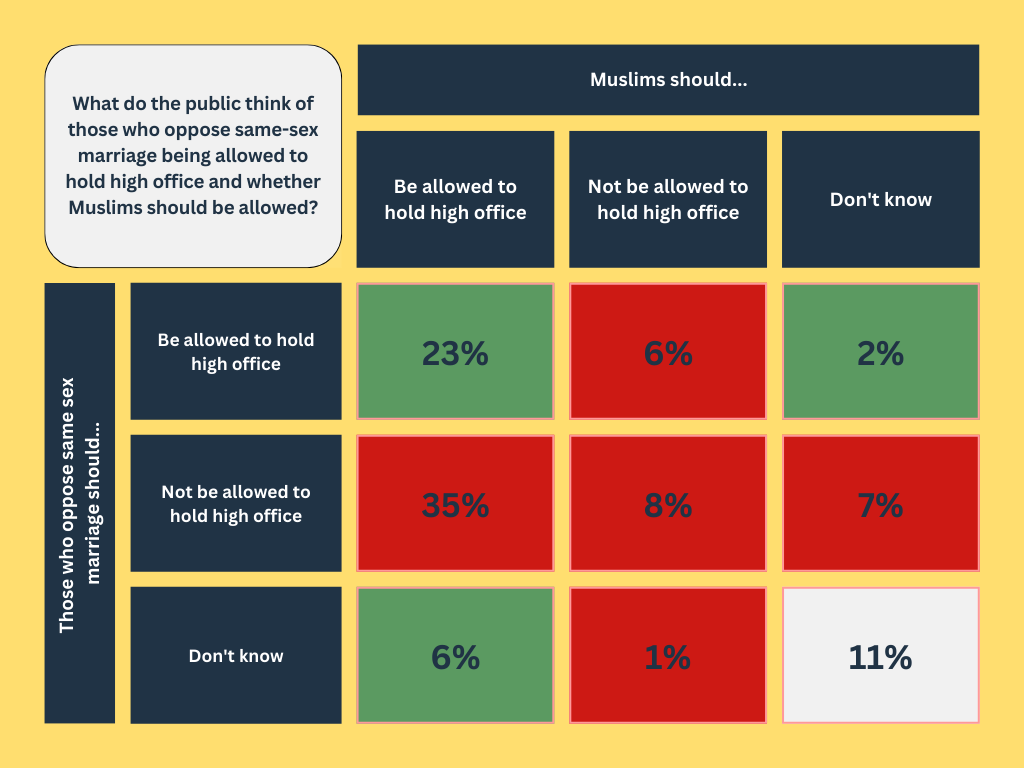

For both Muslims and Evangelical Christians, we fitted every one of our respondents in to one of nine groups – either supporting, opposing, or not knowing whether being religious (Muslim or Evangelical Christian) should prevent someone from being in power, and whether being against same–sex marriage should be prohibitive to being in power. The five red sections show the paths that can be taken to be opposed to a socially conservative religious person in high office: either thinking the religion in and of itself is the issue, or viewing opposition to same–sex marriage as a deal–breaker, or both. The green boxes are those people who would not oppose such a person (or at the very least, who say they would not oppose in response to one question and did not know in response to another).

What the public think of those who oppose same–sex marriage being allowed to hold high office and whether Muslims/Evangelical Christians should be allowed

What do the public think of those who oppose same-sex marriage being allowed to hold high office and whether Evangelical Christians should be allowed?

What do the public think of those who oppose same-sex marriage being allowed to hold high office and whether Muslims should be allowed?

Overall, there is a clear pattern. While only a small minority thinks those that practice Islam or Evangelical Christianity should be banned outright, a larger minority say that opposition to same–sex marriage isn’t compatible with government office. Add those together and you have around 60% opposed to a candidate with socially conservative religious views. This compares to around three in ten being comfortable with such a candidate. The rest are those that don’t know about either.

In other words, those opposed to such candidates outnumber those in favour by 2:1. Plus, once you add in people’s opposition based on views, any apparent differences between the religions basically vanish. The public were, for example, less likely to view being Muslim as, in and of itself, a bar to office. But add in opposition to same–sex marriage, and 57% would oppose a socially conservative Muslim holding high office. The figure for Evangelical Christians is 56%.

We see something similar when we look at abortion. The percentage who would block a socially conservative Muslim is 60%; for a socially conservative evangelical Christian is it 59%.

So (relative) religious tolerance in the abstract is quickly challenged once we get down to the problem that occurs when sincerely held religious beliefs clash with the progressive, secular consensus.

A fear among some religious political figures within broadly progressive political parties – perhaps best summed up in Tim Farron’s lecture to Theos after resigning as Lib Dem leader – is that this trend is only going in one direction.

And, sure enough, when we compare those under 30 with those over 65, we see a significant difference in attitudes. Young people are notably more likely to oppose a socially conservative Evangelical Christian as a political leader than those of pensionable age, and marginally more likely to oppose a Muslim with similar views. Among those aged 18–30, 71% say either being opposed to same–sex marriage or being a Muslim should be a bar from office, and 68% say the same of Evangelical Christians. The respective figures for those over 65 are 47% and 44%.

So we have a situation where religions are deemed acceptable in the abstract, but if practiced a certain way opposition becomes much sharper. For those politicians with sincerely held religious beliefs, this may feel like something of a distinction without a difference. While the public might say they do not mind the idea of a religious politician, the reality when those religious beliefs run against the UK’s increasingly socially progressive society is very different indeed.

This confirms what we know – that religious politicians with socially conservative views will face significant headwinds, particularly in parties which see themselves as progressive. They won’t just face pressure from party or media elites, but also (on the basis of this data) from voters in general. In the future, religious politicians will have to work harder to articulate what the political implications of their faith positions are, and why these can or should be supported by the general public.

Related items

10 December 2024

9 December 2024

6 December 2024