Long Read: 'A Kingdom on the Brink': The 1979 Scottish Referendum

In the first of a three part series of 'Long Reads' to mark the 43rd anniversary of the first referendum on the creation of a Scottish Assembly, Tom Chidwick takes a deep dive into the events leading up to 1 March 1979 and charts the state of Scottish politics in the 1970s.

Estimated Reading Time: 8 minutes.

On 10 January 1979, after a six-day summit in Guadeloupe with President Jimmy Carter, Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, an avuncular British Prime Minister James Callaghan touched down at Heathrow Airport to be met with a pack of the Fourth Estate. With severe frosts and heavy snowfall, a mean temperature of 1⋅17 ºC, a five-day-old unofficial lorry drivers’ strike and speculation that the Government would introduce a ‘State of Emergency’, Britain presented a stark contrast with the sun-drenched archipelago in the Caribbean.

At an impromptu press conference, Callaghan was keen to stress that, due to 'the miracle of modern communications’, he had been in constant touch with Number 10 Downing Street throughout his stay in Guadeloupe. Whilst the PM’s jocularity and easy-going charm had served him well throughout his political career, his positive assertion that there was ‘not mounting chaos’ was a gift to his critics.

For the Daily Telegraph, unlike ‘less august callers’, it was unlikely that the Prime Minister’s telephone calls had been interrupted to ask whether it had been ‘democratically certified by the union executive as a relevant emergency’, nor would Callaghan have experienced ‘crossed lines, unsought connections to the Falkland Isles, unproductive whirring sounds, clicks and silence’.

Whilst Callaghan never actually uttered the immortal words ‘Crisis? What Crisis?’ (they belonged to The Sun’s headline writers), burgeoning disruption as the ‘Winter of Discontent’ took hold came to define his administration and contributed to Labour’s generation out of office. From ‘Labour Isn’t Working’ to ‘New Labour, New Danger’, and ‘Chaos with Ed Miliband’, the spectre of James Callaghan’s much-maligned administration haunted the Labour Party for decades to come.

In recent years, Callaghan’s reputation has undergone significant refurbishment, steadily rising up the not entirely scientific prime ministerial league table, with academics choosing to stress the weak political hand he was dealt, the depth of his ministerial experience and his skills in chairing the Cabinet. For Tony Benn, Callaghan was a ‘very nice guy’ in an ‘impossible position’ who even in turbulent times remained utterly dedicated to ‘a very collective type of decision-making’.

In recent years, Callaghan’s reputation has undergone significant refurbishment, steadily rising up the not entirely scientific prime ministerial league table, with academics choosing to stress the weak political hand he was dealt, the depth of his ministerial experience and his skills in chairing the Cabinet. For Tony Benn, Callaghan was a ‘very nice guy’ in an ‘impossible position’ who even in turbulent times remained utterly dedicated to ‘a very collective type of decision-making’.

In addition to weathering three years without a majority, having to borrow nearly four billion dollars from the International Monetary Fund and enduring the infamous ‘Winter of Discontent’, Callaghan’s premiership also saw Britain embark on a significant programme of constitutional change.

From the Hamilton by-election of 1967, which saw the surprise election of the Scottish National Party’s Winnie Ewing, to the election of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government in May 1979, British politics was confronted with the problem of Scottish estrangement from Westminster and the resulting emergence of the SNP as a significant political force north of the border. Despite the Glasgow Herald’s assertion that ‘only a belief in the incredible allows a win for Mrs Ewing’, her victory by nearly two thousand votes in November 1967 had a dramatic effect on British politics, delivering a body-blow to the Labour Party’s dominance in the West of Scotland and sparking a rush to address the ‘Scottish question’.

Scotland in the Seventies was a nation on the move, grappling with deindustrialisation, a decade of nationwide industrial strife and the discovery of North Sea Oil. The collapse of Scotland’s traditional primary industries in this period also marked the beginning of the end for what William Knox called ‘the male, skilled, industrial, Protestant worker’ north of the border. Concurrently, the ‘modernisation’ of town and city centres, the construction of shopping centres and multi-storey carparks, and the clearance of dilapidated housing was transforming Scotland’s landscape. In the ‘New Town’ of Cumbernauld in North Lanarkshire, one such shopping centre at the heart of the town was memorably described as looking ‘a bit like an oil rig that somehow got stranded on its way from John Brown’s to the North Sea’.

Between 1947 and 1966, the creation of five ‘New Towns’ (including East Kilbride in South Lanarkshire and Glenrothes in Fife, which were renowned for their concrete, Brutalist architecture) to house the country’s urban population living in poor, overcrowded or bombed-out housing also began to affect Scotland’s politics. As the sociologist Douglas S. Robertson once argued, the ‘New Towns’, which disjointed old industrial communities, also undermined traditional party loyalties and resulted in support for the SNP growing among both ‘the skilled working class and small business elements within the middle class’.

Throughout the Seventies, Scottish politics began to diverge from that of the rest of the United Kingdom. Whilst the quality of life of the average Scot steadily improved after 1945, economic dislocation allied to fears about the impact of Britain’s entry to the EEC on Scottish fishing and agriculture as well as a resurgent ‘Scottishness’, encapsulated in the SNP’s ‘It’s Scotland’s Oil’ campaign, presented the first major challenge to Westminster’s hegemony in a generation and aided the election of eleven SNP MPs in October 1974. As the academic and playwright Willy Maley once remarked, the Seventies was also the decade in which many primarily Scottish Labour figures (including Gordon Brown, whose Red Paper on Scotland was released in January 1975) helped crystallise the idea that ‘socialism could profitably be harnessed to a developing Scottish political identity’.

For the Wilson and Callaghan governments, the answer to the complex and seemingly unanswerable Scottish question—which John P. Mackintosh compared to Britain’s need to ‘readjust to a new European role’—was to devolve greater executive and political power to Scotland. The Scotland Act 1978—which was memorably described by a Dumfriesshire bookseller as the ‘world’s worst seller’—was the result of ten years of frenetic debate about giving Scotland greater autonomy from Westminster. The Act proposed creating a Scottish ‘Executive’ and an ‘Assembly’ of 142 members (two for each of Scotland’s existing 71 constituencies). They would be elected by First Past the Post rather than by a proportional system, which many devolutionists favoured.

Although the Scotland Act laid out the powers to be transferred to the Assembly (covering the bulk of Scotland’s social policy, including healthcare, social welfare, education and public sector housing), it did not specify the procedures which would govern its day-to-day life. In both policy and practice, the Assembly would have provided Scots with an opportunity for new thinking and, as one commentator suggested, brought about a ‘willingness to break with the preoccupations of the past’.

To ease the Act’s passage through the House of Commons, the Government also agreed to hold a post-legislative referendum to allow Scots to cast a vote on whether or not to establish a devolved legislature. For Edinburgh’s pro-devolution broadsheet, The Scotsman, although expedient, the Government’s decision set a ‘risky precedent’. It would strengthen the demand that Parliament’s decision ‘on any big issue, especially constitutional, should be confirmed by plebiscite’. The Act also featured a controversial amendment, laid down by native Scot and London Labour backbencher George Cunningham, which required 40 per cent of the eligible electorate to vote ‘Yes’ for it to be put into force. For Donald Stewart, the SNP MP for the Western Isles, Cunningham’s ’40 per cent rule’ was a ‘booby trap’ laid to destroy devolution; even Tam Dalyell, the Assembly’s most ardent opponent, came to regret it, believing that ‘No’ would have obtained a more decisive vote without what appeared to many as an ‘English trick’.

As in 1975, the Government’s (albeit reluctant) support for a referendum demonstrated the Scottish question’s immense disruptive potential to the norms of British governance and highlighted the scale of the task that Callaghan’s administration had taken on. With nearly 3⋅75 million Scots eligible to vote, there would be twelve ‘counting’ regions, which mirrored the geographical areas administered by Scotland’s Regional Councils, with more than 11,000 civil servants operating polling stations and counting ballots across the country.

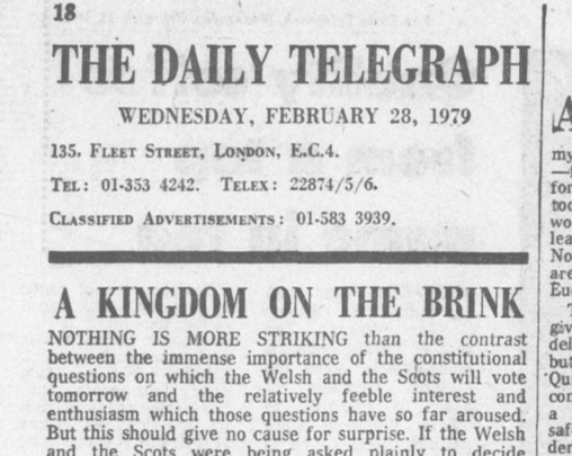

For the critics of devolution, the Government’s attempt to establish new institutions that embodied the distinct political culture north of the border threatened to do irreparable damage to the ties that tethered the United Kingdom’s component nations together. On the day before polling, the Daily Telegraph lamented ‘A Kingdom on the Brink’. It warned its readers that, if Scotland assented to a ‘complex set of constitutional proposals which baffle the head and have no appeal to the heart’, it would be launching Britain on a ‘disaster course from which it is hard to see an escape’.

Jeremy Thorpe, the former Leader of the Liberal Party who would go on trial for conspiracy to murder in May 1979, forecast that devolution could lead to Scotland and Wales’s independence in just five to seven years. Even Terence O’Neill, the antepenultimate Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, suggested that, despite the permanence of the Crown and its shared economy, it was ‘not impossible’ that a long history of ‘reluctant concessions to the “Celtic fringe”‘ could see the United Kingdom simply ‘cease to exist’.

Whilst Harold Wilson and James Callaghan devoted considerable time and energy to devolution in the years leading up to the referendum, many within Scottish Labour were reluctant to establish a Scottish Assembly. As Gerry Hassan has pointed out, the Labour Party in Scotland in the post-war era were consistently anti-Home Rule, ‘implicitly so in the Attlee era, formally so in the Gaitskellite period of the 1950s and defiantly so under the influence of Willie Ross’ (the headmasterly Secretary of State for Scotland) in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

After the Scottish Executive of the Labour Party reaffirmed its opposition to devolution by just one vote in June 1974 and stressed that ‘Scottish difficulties’ would be best solved by greater nationalisation, Ross told the House of Commons that the SNP were ‘conning the people of Scotland into tartan chaos’. Even Gordon Brown, one of the Assembly’s most persuasive advocates, was concerned that the Government’s dogged pursuit of devolution could steer attention away from the country’s most pressing problems, including its ‘unstable economy and unacceptable level of unemployment, chronic inequalities of wealth and power and inadequate social services’.

With the help of Alex Kitson, the Treasurer of the Scottish Trades Union Congress, the Labour Party’s leadership in London, which feared the loss of more marginal seats to the SNP, sanctioned a nationwide arm-twisting campaign as it attempted to convince the Scottish Executive to put its weight behind devolution. At a special conference on devolution on Saturday 17 August 1974—the infamous ‘Battle of Dalintober Street’, which remains the stuff of legend within Scottish Labour—a fierce and emotional debate resulted in a majority for Labour’s devolutionists, with one delegate from Maryhill stressing that the Party needed to combine devolution with a renewed focus on tackling the country’s social and economic problems by adopting ‘policies which eliminate fear of want, bad housing and fear of minority oppression’.

For Tam Dalyell, ‘Dalintober Street’—which Andrew Marr once memorably remarked is ‘generally intoned with a mixture of awe and regret, as if it were the scene of some Chicago gangland massacre’—was simply ‘a bad, bad day’, believing devolution to be ‘little more than a political life jacket – and a life jacket, what’s more, that will not inflate at the right time’. As Scots went to the polls to cast their verdict on the Scotland Act, the fate of the United Kingdom rested on Scotland embracing Wilson and Callaghan’s life jacket, with the Prime Minister lamenting the unlimited number of ‘uncharted rocks that can wreck this particular freighter during its voyage’. Perhaps prophetically though, as a snowy morning broke on 1 March 1979, the Bee Gees' 'Tragedy' topped the Charts come ‘Referendum Day’.

Tom Chidwick is the Manager of the Mile End Institute and a contemporary historian. This essay originally appeared in Tides of History and is reproduced with their kind permission.

.jfif)