Should No.10 prepare for a ‘war on woke’? Professor Tim Bale

According to research published this week, it is underlying socio and cultural (as opposed to economic) values that keep the Conservative Party and its electoral coalition together and give it the best chance of connecting with the voters it will need to win again in 2024.

Political scientists often make use of two sets of questions to measure people’s economic and social values. They’re designed to tap into underlying, stable, long-term ideological attitudes rather than ephemeral, short-term policy preferences.

The first set covers economic values: the distribution of wealth and income, big business, fairness, etc. The second covers socio-cultural values and includes question on things like law and order, the purpose of education, respect for traditional values, and censorship.

Essentially, this is a recognition that politics can’t just be understood as a contest between Left and Right – between state and market. We also have to take into account whether people are socially liberal or social conservative.

Most of the time, those questions are only asked of voters – for instance by the gold standard British Election Study. But in this new study they were also asked of MPs and grassroots party members from both the Conservative and the Labour parties.

Their responses give us a sense, not just of how united or divided the parties are, but of how out of touch they are with voters – and not just voters in general but even those voters who supported them at last year’s general election.

Covid-19 is going to do some serious damage to the economy. And one only has to look back to events like Black Wednesday in 1992 and the financial crash of 2008 to see how easily that sort of setback can swiftly shred a party’s hard-won reputation for economic competence.

If (some would even say when) that happens to the Tories in the months and years to come, then, the research suggests, they’re going to have to rely heavily on social and cultural conservativism to see them safely through the next election.

That’s because, when it comes to economic values, the Conservatives a) are less likely to see eye-to-eye with one another than their Labour counterparts and b) are further away, if not from the average voter, then from the voters that helped them win so comfortably in 2019.

Indeed, those voters’ underlying values on the economy mean they have more in common with the Labour Party at all levels than they do with Conservative members, activists and MPs.

True, on social and cultural values, the Tories are not altogether united either. But they are much closer to voters – especially the ones they really need to keep hold of if they are to repeat their 2019 win in four years’ time.

Let’s look, first, at economic values. Figure 1 shows that on every question used to tap into those values apart from the first one on redistribution, the differences between what the Conservative Party’s MPs, grassroots members and voters are much bigger than they are between Labour’s people.

Figure 1

It also shows, incidentally, that, if Labour can overcome the economic competence deficit that has cost it so dear since 2010, and then get voters to realise just how differently Tory MPs think about the economy than they themselves do, then the Government could find itself in serious trouble.

Figure 2 hammers home that warning. On every economic values question, the average voter who made the journey from Labour in 2017 to Conservative in 2019 (represented by the black dot) is more Left-wing than the average member of the public, as well as noticeably to the Left of the average individual who voted Conservative in 2019.

Figure 2

Moreover, these 2019 Labour-to-Conservative switchers are far, far closer to Labour when it comes to underlying economic values than they are to the Conservatives.

For instance, a full 81% of those switchers think that big business takes advantage of ordinary people – very much in line with 83% of Labour MPs and 92% of Labour members, but very much out of line with Tory members and Tory MPs, only 34% and 18% of whom, respectively, think the same way.

And on whether “there is one law for the rich and one law for the poor” the 84% of Labour-to-Conservative switchers who agree are far closer to the 92% of Labour members and the 71% of Labour MPs who say the same than they are to the 22% of Tory members and 5% of Tory MPs who think so too.

Keir Starmer might have sacked Rebecca Long-Bailey last week but he’s no neoliberal, and nor is his Shadow Chancellor Anneliese Dodds. They will be perfectly comfortable putting forward an economic recovery plan that reflects those switchers’ values. Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak? Not so much.

Any conversion to socialism brought on by the current emergency will, one suspects, be short-lived, leaving the party — on the economy at least — stranded way to the right of many of the voters they need to hold onto.

But when it comes to social and cultural values, it’s a whole different story – and a story with what could well be a happier ending for the Conservatives.

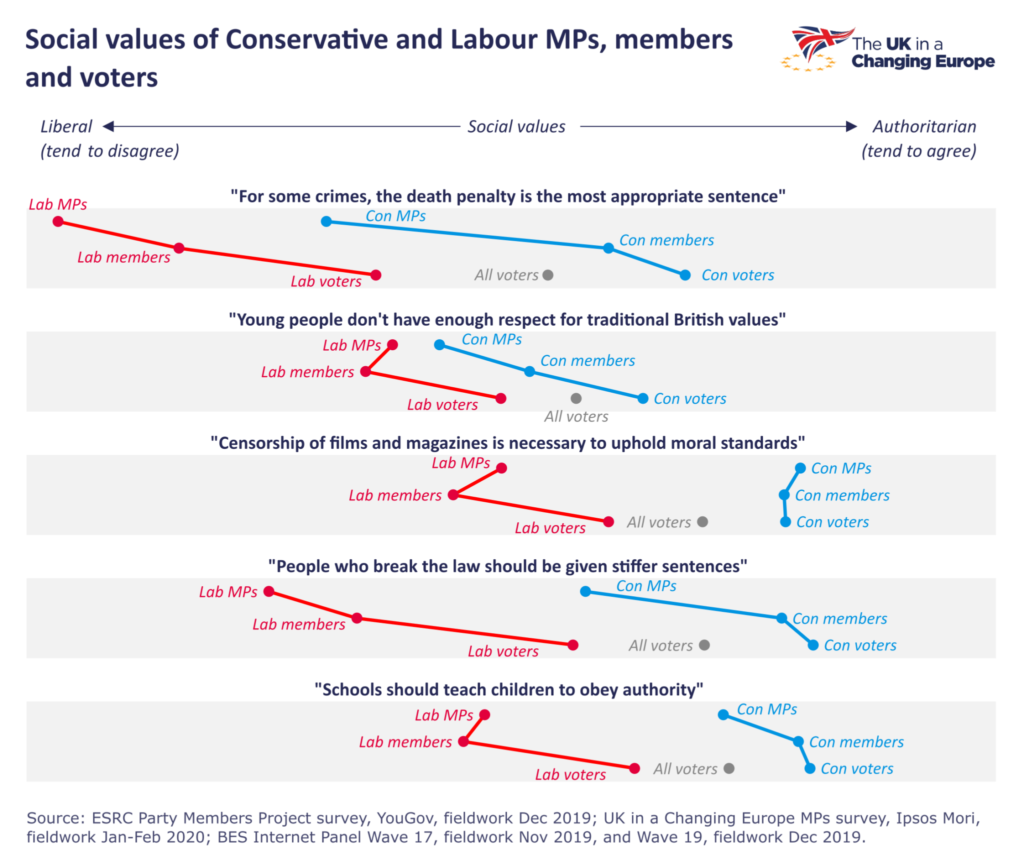

Figure 3

For one thing, as Figure 3 shows, generally speaking (the exception being the death penalty), the Conservative Party’s MPs, members and voters are more united than their Labour counterparts and, as a whole, tend to be a little closer to the average British voter.

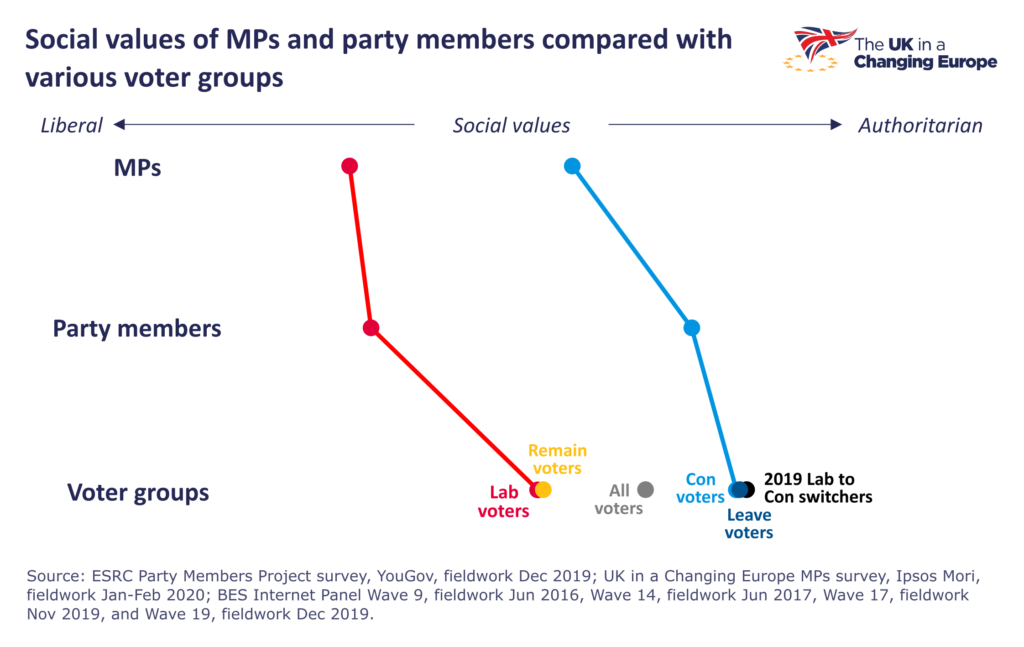

For another, when we look at different groups of voters, as we do in Figure 4, we can see that — in what is essentially a mirror image of the picture on economic values — 2019 Labour-to-Conservative switchers (again represented by the black dot) are much, much closer to the Conservatives when it comes to underlying social/cultural values than they are to Labour. In fact, those switchers even sit to the right of Conservative members and Conservative MPs.

Figure 4

Ultimately, though, it is the yawning gap between the 2019 switchers and the Labour Party they abandoned that is most striking. Just 17% of Labour members and 9% of Labour MPs think that “young people don’t have enough respect for traditional British values” — a view held by 88% of Labour-to-Conservative switchers.

The idea that schools should teach children to obey authority is supported by 81% of those swing voters, against just 29% of members and 41% of Labour MPs. Stiffer sentences are supported by 85% of switchers — again way more than is the case for Labour members (25%) and Labour MPs (24%).

It is also striking, again from Figure 4, but this time looking solely at parliamentarians (who are, after all, the most visible representatives of their respective parties as far as voters are concerned), that Tory MPs are far closer not just to their voters but to all voters, than are Labour MPs.

That’s because, much as it pains liberals to admit it and even if things may gradually be shifting their way through generational change, Brits remain a pretty authoritarian bunch.

Given all this, some kind of culture war, however damaging and polarising some fear it would be, is arguably a perfectly rational strategic choice for the Conservatives in the years to come.

It would build on — but, just as crucially now that Brexit is nearly done, allow them to build out of — the Leave-Remain identities established, to their obvious recent advantage, since 2016.

Pushing back against supposed attempts by the liberal elite to make Brits ashamed of their history and downplaying structural and institutional racism are only the more obvious aspects of such a strategy. Clamping down on illegal immigration — especially now that Nigel Farage is back punching that particular bruise — will also loom large.

Even apparently trivial interventions, such as Gavin Williamson’s call for schools to insist pupils face the front and pay attention to the teacher rather than each other play a part.

There are, however, just a couple of crucial caveats.

First, it takes two to tango: while there may be plenty of socially liberal Labour MPs who might easily be tempted to fall into a Tory trap on this score, for example by allowing it to look like they were lecturing Home Secretary, Priti Patel, on racism.

Keir Starmer and most of his Shadow Cabinet, whatever their true feelings, seem far less likely to take the bait.

Second, but no less important, the figures above suggest that Conservative MPs are not only more socially liberal than Conservative grassroots members and Conservative voters but more liberal than most voters – and on some issues are even more liberal than Labour voters.

But to win a culture war, like any other war, a general not only needs all his troops behind him but they all have to be up for the fight.

By Professor Tim Bale, co-director of the Mile End Institute and deputy director of the UK in a Changing Europe.

This piece was originally published by Unherd.

Read the Mind the values gap report.