How a handful of Tory activists prevented a change in the Conservative Party's leadership rules

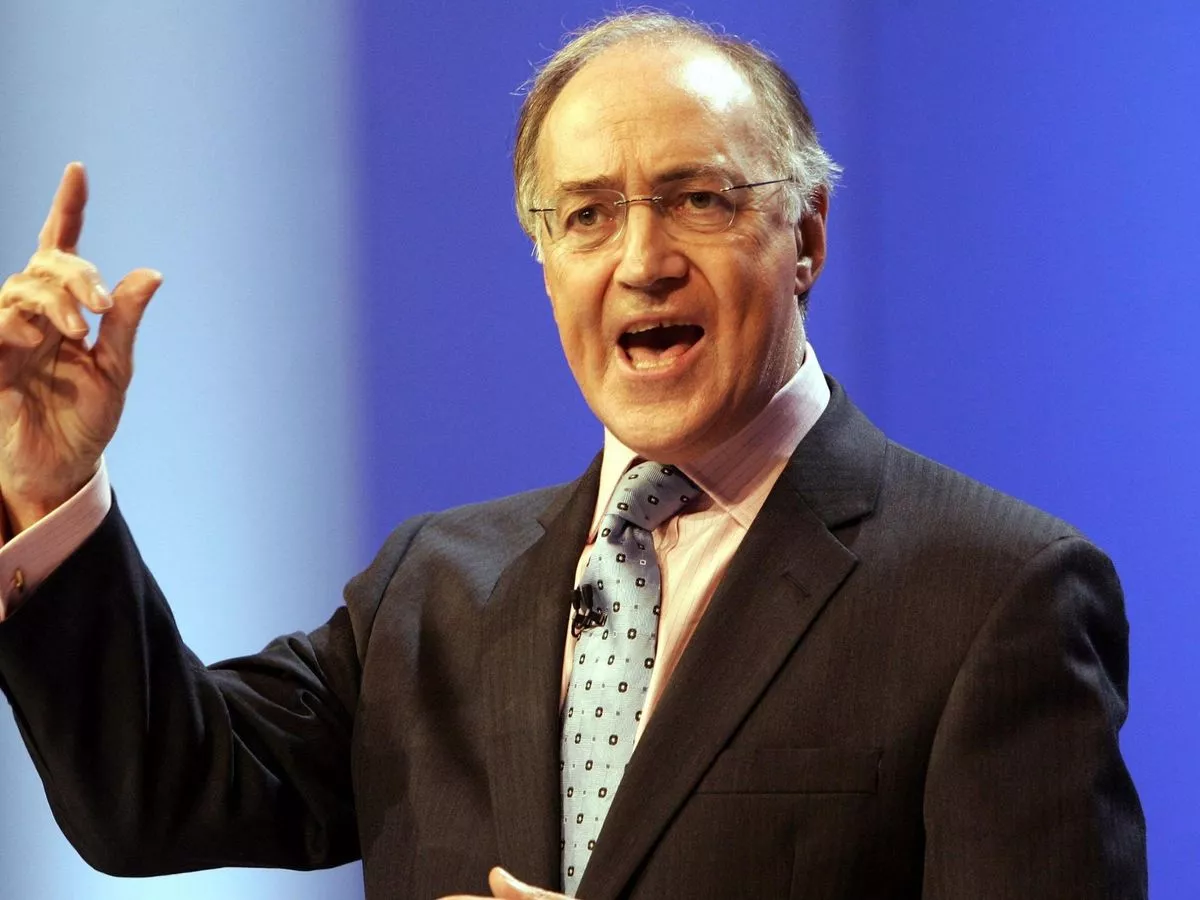

With the next general election fast approaching, Lee David Evans looks back to the aftermath of the 2005 election when the outgoing Conservative Party leader, Michael Howard, attempted to fundamentally reform his party's internal democracy.

Estimated Reading Time: 4-6 minutes.

The 2005 general election was a bruising contest for the Conservative Party. Tony Blair’s ‘New Labour’ defeated the Conservatives for the third successive election; to rub salt in Tory wounds, under Michael Howard’s leadership the party had recovered to only its third worst vote share since the Great Reform Act of 1832. (The status of worst and runner-up belongs to 1997 and 2001, respectively). Howard followed the example of fellow defeated leaders John Major and William Hague and announced that he would be resigning as leader of the party: ‘I said that if people do not deliver they go, and for me, delivering meant winning the election. I did not do that… I want to do now what is best for my party and over all, for my country'.

What Howard thought best for his party was not, however, an immediate exit from the political stage. He had one final thing he wanted to achieve as leader. Howard had only become leader in 2003 because his predecessor Iain Duncan Smith, commonly known by the initialism IDS, lost the confidence of Tory MPs. IDS was the first leader elected under the post-1998 leadership rules which empowered the party’s members to make the final decision over who led them by choosing between the MPs’ two favoured candidates. (In 2001, IDS defeated former Chancellor and prolific europhile Ken Clarke). Many in the party, including Howard, felt the experiment in internal party democracy had not gone well. ‘There is a good deal of dissatisfaction with the existing rules for choosing the leader of the party,’ Howard told the press. ‘So I intend to stay as leader until the party has had the opportunity to consider whether it wishes the rules to be changed and if so, how they should be changed.’

Howard moved at pace to present his alternative plans, publishing A 21st Century Party mere weeks after voters had been to the polls. The document slammed the leadership election model (which is still in use today) as ‘expensive and protracted, causing maximum uncertainty and disruption’. It went on to say that ‘members cannot know the candidates as well as the MPs’ and argued ‘it is essential that the leader enjoys the confidence of Conservative MPs’. Perhaps most fundamentally, the paper said it was ‘wrong in principle and certainly damaging in practice for one group of people to have the power to elect the leader of the party and a different group of people to have the power to remove him or her.’1 In place of the member-centric model that had delivered IDS the leadership, a wholly new means of electing the leader was proposed.

Under Howard’s proposals, candidates would need the support of 10% of MPs to be nominated. If a candidate was nominated by more than half of all MPs, the leadership election would be over - they were the winner. If no candidate achieved that threshold, validly nominated candidates would each address and answer questions from the National Convention, the name given to the party’s most senior volunteers. Members of the convention would then vote on which of the candidates should lead the party.

So far, so simple - but that wasn’t the end of matters. The grassroots’ ballot would not be definitive. The outcome of the National Convention vote would be published, but the decision as to who should lead the party would then go back to MPs, who would make the final choice by a method of balloting determined by the 1922 Committee. The only guarantee for the candidate who won the backing of the National Convention was a place in every round of voting, including the final one. But MPs could elect someone else leader, if they wished.

The Howard proposals were an attempt to consult the upper echelons of the party’s grassroots without giving them, or members more generally, the final say over who became leader. But in the eyes of many the suggested model was confused and risked creating competing mandates if the grassroots’ favourite and the MPs’ chosen leader diverged. The proposals also suffered from being bundled together with other party reforms, widely interpreted as an attack on the rights of local Conservative associations.2 David Cameron recalls that the proposals for change ‘went down badly with both the membership and a significant number of MPs.’3 Other MPs, including the perennially eccentric former Shadow Home Secretary Ann Widdecombe, said the proposals would make the most successful party in western politics a ‘Stalinist centrally controlled set-up’.4 Amidst this febrile atmosphere, the 1922 Committee met to consider the proposals on 15th May 2005 and resoundingly rejected them. Instead, approximately 100 of the 180 MPs at their meeting backed an alternative proposed by the Committee’s executive.

Howard’s proposed leadership rules were dead - but some of the principles contained within them were not. Under the 1922’s alternatives proposals, the role of the membership would be similarly advisory, but less formalised. They recommended that fewer MPs should be required to nominate a valid candidate - just 5% - and once nominations closed a two-week consultation of the party’s grassroots would begin. MPs would discuss the leadership election with their constituency parties as well as local elected officials, with the outcome of these consultations reported to the chairman of the 1922 Committee. He or she, and it’s always been a ‘he’ so far, would then inform MPs of which two candidates were deemed the most popular. With the views of members’ ringing in their ears, a series of ballots would then be held among MPs. The candidate with the lowest number of votes would be eliminated in each ballot until one candidate remained: the new leader.

Conservative MPs voted to endorse the 1922 Committee’s alternative model by 127 votes to 50. But some people who would play a very prominent role in the party’s future were concerned. David Willetts, Michael Gove, Theresa May and Iain Duncan Smith, all either keen to win the affections of grassroots members or overcome with regard for internal party democracy (or both), joined other Tory MPs in authoring a letter to the Daily Telegraph arguing that ‘members deserve more than an ill-defined consultation mechanism’ and urging their colleagues:

It is not too late for the parliamentary party to find a way of involving grassroots members in the Conservative Party’s most important decisions. Any proposals that do not facilitate democratic involvement deserve to be defeated.

The proposed changes would not be adopted without the consent of those very grassroots, however. According to the 1998 Conservative Party Constitution, the rules would only be amended if the Constitutional College of the party - comprising MPs, MEPs, senior peers and key members of the voluntary party, with activists holding a majority - said so. To be adopted, the proposals (which were eventually put to a vote independent of the wider party reforms originally proposed in A 21st Century Party) needed to win majority support from the entire college, as well as a two-thirds supermajority among MPs and activists. 1,141 people could vote by post - and 1,001, or 87.7% of them, did.

Among MPs, from whom (via the 1922 Committee) the proposals had originated, the threshold was easily met: 71.4% of MPs voted in favour. The required simple majority of senior Lords and MEPs supported the proposals, too, with 58.5% voting for change. Yet whilst more than half of the National Convention voted to strip themselves of their formal role in the election of a leader, it wasn’t enough. With 63.5% support among the grassroots, the changes were defeated. The support of just a few dozen more senior activists would have ended the members’ ballot in leadership elections after just one cycle.

The final few months of Michael Howard’s leadership were dominated by this chaotic and divisive debate. Yet the party soon learned to put these frictions behind it when, unlike in 2001, the members voted for the leadership candidate most heavily favoured by MPs: David Cameron. He took on the mantle of his party in December 2005 and led without any serious challenge to his authority for eleven years. Few people raised the prospect of changing the leadership election rules during his tenure at the top. Yet the rapid succession of leaders since his departure in 2016 has caused some in the Conservative Party to wonder, once again, whether the demands of being ‘a 21st century party’ require the leadership rules to be reformed.

References:

- Peter Snowdon, Back from the Brink (HarperPress, 2010), p. 184.

- Tim Bale, The Conservative Party: From Thatcher to Cameron (Polity, 2010), p. 260.

- David Cameron, For the Record (William Collins, 2019), p. 78.

- Snowdon, Op. cit., p. 185.

Lee David Evans is the John Ramsden Fellow at the Mile End Institute.