Research and Academic Writing

This section of the Blog will include excerpts and reflections from third-year Research Projects and postgraduate dissertations. Please do get in touch with other ideas as well!

This artwork was inspired by studying the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice in Ovid's Metamorphoses and modern retellings as part of the COM4209 module. It also incorporates Papula's interest in the symbolism of flowers.

"I chose to put eyeballs in the yellow carnations (which can symbolise disappointment and rejection) to highlight the act of Orpheus looking back (and maybe even the male gaze which sees women as passive objects). Orpheus himself doesn't have eyes to also allude to his regret. The roses behind Orpheus were also to hint at his general relationship to love and grief in his romantic life."

Papula Khorshid (1st year undergraduate student)

When we consume literature, can we be so immersed in it that we end up being consumed? This question and more specifically its affirmative answer is the starting point of the story of Miguel de Cervantes’s “Don Quijote”. Among other things, the author addresses the theme of literature and plays with the negative consequences it can have on its consumers.

Don Quijote, a poor inhabitant of the countryside, is so immersed in his chivalric romances that he comes to construct his own reality based on these inspirations. Thus, he cannot distinguish the real world any more and all his interactions are centred around his new identity as a knight who has the duty to save his beloved and help poor people who have suffered under unjust conditions along the way. Spread across more than 1000 pages and two parts, the reader witnesses his three journeys filled with peculiar adventures.

Although Don Quijote is trapped in his made-up world, many of the people he encounters play along with his story and thus make him even more confident in his consciousness about reality. This comical element contributes to the fading of the lines between appearance and reality. The character of Don Quijote himself is another constant element of comic relief throughout the plot: he is an old, frail man riding on ‘Rocinante’, his even more fragile and bony horse, and he is accompanied by his friend Sancho Panza whose last name is a reference to his big belly. The latter rides on a small donkey and helps Don Quijote through the sometimes dangerous situations his master puts them in.

The novel was published in 1605 and the second part appeared ten years after the first one, following the initial success of Quijote’s story. In this second part, Cervantes uses a truly modern and revolutionizing narrative technique for his time: the characters that the protagonist encounters in the second half have read his story and thus know of him. Thus, the author deeply interferes with what the reader can interpret as the reality of the plot and what Don Quijote makes out to be his own reality: in a way, the fictional plot becomes real throughout the novel.

The entire story, in addition to its timeline and its narrator(s), is also a rather complex matter: the narrator of the first part addresses the fact that the text is translated from the Arabic and makes numerous references to its original author Cide Hamete Benengeli. Moreover, in the second part, Don Quijote and Sancho Panza make remarks about the accuracy and faults they judge in the novel which has been published about them. Here, Cervantes, again, adds another layer of meaning by making in-text comments about what it means to write about other people, as well as what the act of translation truly entails.

To judge the poor old adventurer as mad based on his crazy beliefs and actions would be too simple and naïve of an assumption to make. In fact, his odyssey deals with numerous other deeper questions about real everyday life that make an analysis of the story a deeply complex one. Apart from being the first “modern” novel using the beforementioned narrative techniques, as well as the most famous piece of literature in the Spanish canon, it also proves to be a very funny read, making numerous ironic references to Spanish traditions, life and State affairs. So, in conclusion, the tale of Don Quijote and his friend Sancho Panza are part of an exciting and fantastically rich piece of literature which I would recommend to anyone looking for a funny and unconventional longer read. And who knows, maybe you will find yourself just as consumed by this novel like I was and like Don Quijote himself is in the beginning?

Laura Ruiz Viejobueno

Comparative Literature and Culture Resources: The National Theatre Collection

Ben Ayaydin (2021 graduate of Comparative Literature and Culture BA course)

The National Theatre Collection is a fantastic platform featuring 40 recorded productions ranging from Greek classics to literary adaptations. You have all the staples such as Macbeth, Othello, The Cherry Orchard to name a few as well as some of the National’s more recent hits such as Barber Shop Chronicles. A further 10 titles are coming to the platform in February.

Many of these productions have accompanying written and filmed learning resources that include rehearsal diaries, archive materials and interviews with cast and creative team.

When studying a play, one of the main problems I find is trying to visualise the performance. You may be able to understand the play from a written standpoint, but since theatre is a visual medium, something is lost when trying to analyse a play solely from the script.

Another thing I have struggled with is trying to find primary and secondary sources that tie into your argument and analysis, and ending up trawling through the library catalogue in the hopes of finding something relevant.

I would often find myself skimming through books in the hope that the author would mention the theme I wanted to discuss in reference to the play I was analysing, only to reach the end with neither being mentioned together.

The National Theatre Collection helps solve and alleviate many of these problems.

Everything you need to critique and understand the plays, from an academic perspective, is all in one place. A vast number of the plays in the catalogue have accompanying supplementary material, which really allows you to delve deeper into them.

The recordings of the plays are fantastically produced and help to capture some of the atmosphere of the performances experienced by the audience. This in turn helps you to visualise how certain scenes play out as well as the use of direction, set design, lighting and costume – all elements that you simply do not get from just reading the script.

Once you have clicked on a play, the additional learning resources are located just underneath the viewing window, giving you a central location to engage with these materials without having to fish around and search for them. In addition, to the left of the viewing window you have a breakdown of the ‘Genre and Form’, ‘Period (First Performed)’, ‘Themes’, and ‘Setting’, with these categories not only providing more insight into the context of any given play but enabling you to find other similar plays thus providing you with a point of comparison.

Under this category breakdown is a list of related content, making it even easier to collate your sources and research in one place, as well as a link to more learning resources. Lastly, there is a full cast and crew list so that you can refer to specific individuals should you want to comment on an actor or an aspect of the creative design within your analysis.

For instance, Othello features an interview with the director Nicholas Hytner in which he discusses the various themes of the play and some of the decisions taken in adapting the play for a contemporary audience.

In addition, there is a character breakdown of Iago and Othello by their respective actors, discussing some of their interpretations of the characters they portray.

Lastly, there is also a feature on ‘Emilia and Desdemona: Women in Othello’, incredibly useful thematic reference material for analysing the plays, particularly if you wanted to do a feminist reading of the production.

All these resources have accompanying transcripts with them which makes referencing really easy as you can quote directly from the transcript.

As a Comparative Literature student, this platform is great for visualising various plays as well as providing a launch pad to discuss wider themes of comparison with other plays through the ‘Subjects’ section. The platform boasts a couple of the plays we have studied, from Brian Friel’s Translations for ‘The Scene of Learning’ to Romeo and Juliet for ‘To Be Continued: Adaptations of Global Literary Classics’, and with the National Theatre constantly adding to the catalogue, the options available to you will only increase.

No matter whether you are a literature student, drama student or just someone who wants to watch quality theatre, this platform is fantastic for everyone.

So how do you access all this for free using your QM login?

- Go to Google and search National Theatre Collection

- Click on the link from the website Drama online library or alternatively follow the link here: https://www.dramaonlinelibrary.com/national-theatre-collection

- Once on the page, click on the Pantheon symbol in the top right corner titled ‘Log in’

- Under ‘Helpful Tips’ click on the link to ‘Shibboleth Login Page’

- Type Queen Mary University of London into the institution search bar then you will see the familiar QMUL log in portal

- Once you’ve done that, you are set to browse the collection to your heart’s content. If a play has additional resources, it’ll appear underneath the viewing window.

Enjoy!

Ben Ayaydin

What is myth? How are ancient myths relevant today?

'Whilst ancient myths may typically be viewed as belonging to an elite — for instance, people who have benefited from a classical education — Morales seeks robustly to challenge this notion. However, far from shying away from the problematic ideological and political history of myth, Morales instead highlights the darker issues which continue to haunt today’s culture.’

Helen Morales’ Antigone Rising: The Subversive Power of Ancient Myths (Wildfire, 2020) is much more than an explanation of Sophocles’ ancient Greek tragedy Antigone. Rather, Morales utilises the spirit of Antigone to investigate the powerful nature of myths, and how there are traces that still linger in today’s contemporary culture. Not only does she explore how myth still contributes to attitudes in today’s societies, but she also investigates how they can be used for positive change. However, perhaps her greatest point is challenging the notion that myth is for the few: she makes a strong argument that, actually, myth is for all.

Read more in Abbie's review for New Classicists (March 2021, Issue 5: free & open-access journal)

For my final year research project, I chose to focus on women travel writers from the nineteenth century. I then narrowed this down to Korean writer Kim Keum-Won and British writer Isabella Bishop to see how these particular writers broke gender conventions of the time and explore their motivations for travel.

My interest in nineteenth century Korean literature stems from my year abroad at Seoul National University in which I was introduced to a variety of new works. After returning to the UK, I found it difficult to find East Asian literature which was translated into English: this was especially true for texts written by women. From then onwards I became determined to focus my dissertation on women’s writing and to uncover some of these lost voices.

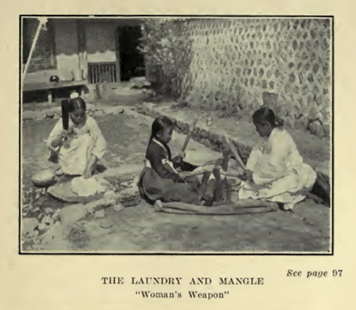

'The Laundry and the Mangle: "Woman's Weapon"': Horace Allen, Things Korean, (New York: F. H. Revell Co, [1908]), p. 109.

I selected this image from Horace Allen’s Things Korean as the front cover for my dissertation as it perfectly encapsulates the gender expectations of Korean women – and arguably women across the world – at the time. Women were forced to remain in the domestic sphere and taught that their power stemmed from their domiciliary duties.

During the research project module, we were asked to prepare an abstract which briefly summarised our dissertation and identify keywords which were used throughout our papers. These abstracts were really useful in illuminating the main points for our project and highlighting our thesis.

Abstract:

This project is an examination of the ways in which Isabella Bishop and Kim Keum-Won use travel to reclaim their narratives by redefining what it means to be a nineteenth century woman. Research often depicts women travellers as travelling with the purpose of escaping the household; however, this study seeks to challenge this conception and present women as active agents in their lives. Building off the research of Susan Bassnett and Dunlaith Bird, Adrift Women asks: How does the works of Isabella Bishop’s Korea and her Neighbours and Kim Keum-Won’s ‘Ho-Dong-Seo-Nak-Ki’ reveal the figure of the empowered travel writer?

Based on a review of Bishop’s Korea and her Neighbours and Kim’s ‘Ho-Dong-Seo-Nak-Ki’, I found that, despite the many differences women across these two contexts face, their experience of dismissal, suppression, and rejection remained the same. Likewise, the comparison between the two highlighted that the figure of the empowered woman travel writer is universal and should be normalised. Further research on women travellers who supposedly travel for escapist purposes are needed to further challenge the notion of the woman ‘in-flight’ of domesticity and strengthen my argument.