An interview with Victoria Cooper and Mimi Tatlow-Golden about their edited collection, An Introduction to Childhood and Youth Studies and Psychology

Our member, Dr. Victoria Cooper (Open University, UK), and her co-editor, Dr. Mimi Tatlow-Golden (both from the Open University, UK), talk about their edited collection, An Introduction to Childhood and Youth Studies and Psychology (Routledge, 2023).

Q: What is this edited collection about?

This 14-chapter collection is novel in drawing together both Childhood and Youth studies and Psychology to explore and understand children and young people’s experiences. Two chapters introduce these two key disciplines of childhood and youth, separately, after which, in 12 thematic chapters, the authors weave together insights from both disciplines. The themes they examine include, among others: embodied childhoods; the development of self; disabled childhoods and youth; diverse families; education; mental health; race/ism and ethnicity; gender in childhood and youth; digital childhoods and youth; and transitioning into adulthood.

The book exemplifies the approach of ‘dialoguing across difference’ that interdisciplinary psychologist Mimi Tatlow-Golden and social anthropologist Heather Montgomery (2020) made the case for in a Themed Section of Children & Society. In placing the disciplines in conversation with one another, we now describe and integrate multiple research approaches to illuminate childhoods and youth, with an emphasis on hearing from children and young people themselves.

Chapter authors are diverse scholars of childhood and youth reflecting established scholars and early career researchers, academics and practitioners from the Global North and South: Heather Montgomery, Afua Twum-Danso Imoh, Anthony Gunter, Naomi Holford, Kieron Sheehy, Budiyanto, Victoria Cooper, Mimi Tatlow-Golden, Mel Green, Lucy Caton, Sri Widayati, Khofidotur Rofiah, Amber Fensham-Smith, Vicky Preece, and Michael Boampong.

Q: What made you initiate this volume?

The work evolved from our shared interest in the experiences of children and young people and a commitment from all our contributors to share research about childhood and youth in ways that can challenge assumptions about what a ‘good childhood’ means, and which can generate rich understandings about the nuances of childhood.

As an introductory text to two key disciplines seeking to understand childhood and youth, the volume has wide-ranging appeal. Its interdisciplinary stance supports considerations of how childhood and youth is experienced differently around the world, shaped by social and cultural contexts; of child rights; and examples within each chapter which engage with children/young people. Critical reflection lies at its heart, a process through which we have brought together diverse academic authors, global professional practices, and voices of children and young people to provide insights and understanding into complexities of childhood and youth.

We wanted to explore some contemporary topics which can be considered sensitive and yet which provide important understandings about the nature and experience of childhood and youth including race and gender. As an example, Victoria Cooper and Vicky Preece’s chapter on embodied childhoods considers how bodies, typically thought of as biological, are also social. It invites readers to think about how children view and understand their own bodies as well as how their bodies are labelled, ‘othered’ and often judged according to size, race/ethnicity, and gender.

An excerpt from Chapter 3 (‘Children’s bodies’), by Victoria Cooper and Vicky Preece:

As a primary site of identity, physical changes in the body across childhood and adolescence have a significant impact on how a child or young person views themself and their emerging identity and also influences how they are seen by others and their expectations of them. Bodies can be sites for concern for parents and carers, professionals, and also children. … [and can be] a means through which children (and adults) make judgements and in which bodies become labelled as different, less than, or broken. This can be used as a way of ‘othering’ children – who may then become ostracised, bullied, and marginalised as a consequence.

…

Judgements about bodies are marked by assumptions made about their gender, their race, their ethnicity, their class, and their natural abilities ( Weiss, 2013 ), as well as their age and perceived attractiveness. As a process of ‘othering’, children’s bodies can be categorised as tall, small, thin, or fat and set apart as different in some way. Chapter 8 examines how the way in which people talk about and understand disabled children reflects implicit beliefs about the nature of difference and disability which goes on to affect how these children are treated. Take for example the experience of dwarfism.

…

Bodies can be weakened, become ill, or damaged, and children can put their bodies at risk. Bodies can be embarrassing; they can break social rules and can become the subject of concern over how they should be seen and how they should behave. As sites for concern, children’s bodies are surveilled and monitored by adults built upon the premise that they require protection, safeguarding, and control – under the guise of what Valerie Steeves and Owain Jones (2010, p. 187) define as ‘surveillance as care’. Analysis of how bodies are seemingly controlled by adults unveils the power dynamic between children and adults and where adults often wield most power.

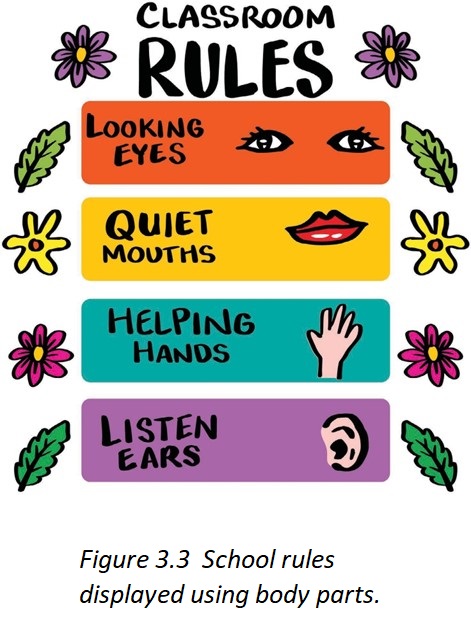

Kate Cregan and Denise Cuthbert (2014) argue that young people’s bodies are often sites for both concern and control. They describe, for example, how young people are viewed as capable and as having the right to choose how they manage, use, and place their own bodies – medically, sexually, and often in areas which pose risks. Yet in another sense, risks such as drug use and sexual encounters cause concern about the ways young people use their bodies. Palmer (2015, p. 25) argues that children’s and young people’s bodies are thus regulated and controlled through different media, including literature and music, as well as through adult-pupil interactions based on ideas about how children and young people should look, behave, and use their bodies. Through her research with school-age children, Palmer describes how these ideas begin during the early stages of education and schooling, where children’s bodies are often required to be ‘ordered, tidy, and neatly presented’.

Regulating the body begins at home with learning to eat, wash, dress, and use the toilet, but starting school is a time when the demands on the body become more prescribed. Being able to meet these demands successfully is necessary if children are to show they have become a ‘good’ school child (Preece, 2021). Schooling the body involves learning to sit still in the correct position, how and when to speak or be silent, and how to regulate bodily functions, such as eating and going to the toilet at the correct times of the day.

School is thus a space where power is exerted over children. The UK and Ireland have among the youngest school-starting ages worldwide (Sharp, 2002). Although the statutory starting age is the term after children are five years old, the majority start school when they are four. Vicky Preece’s (2021) research, which focused on children’s lived experience of starting infant school in England, reveals that a key element for these 4-year-olds centred around the physicality of the experience and how bodies are schooled. The following case study extract illustrates these experiences and are taken from some of Preece’s ethnographic field notes and observations that were carried out in the first few weeks of the children entering school.